Larry Swedroe makes the case that the value premium should always exist . Others agree, insisting that even the small cap premium will endure. Ben Carlson makes the fair case that it is unknowable. There are many others offering their own thoughts on the idea. Allow me to be so bold as to chime in.

The Value Premium

I think so (at least before trading costs). Here’s why:

The value premium is a relative premium which – I believe – exists because of mean inversion. (Mean inversion is the idea that what goes up will go down even farther from where it started.) Because some stocks will always have a relatively higher Price/Book (or earnings, etc.) ratio than others, there will always be the opportunity to purchase something relatively cheaper temporarily. If prices fluctuate and book value (or earnings, etc.) remain relatively fixed, there is will always be a point in time when you can purchase the thing stock is priced relatively low compared its value.

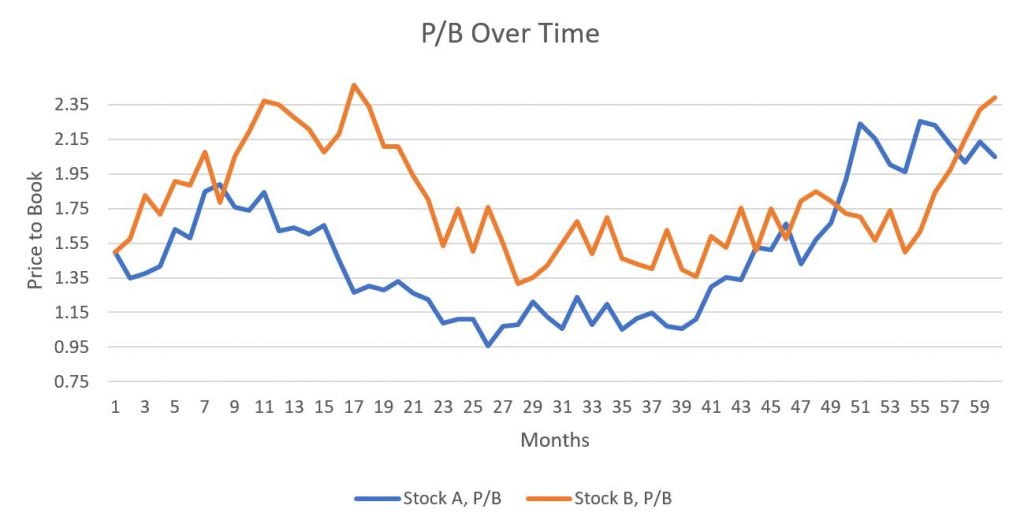

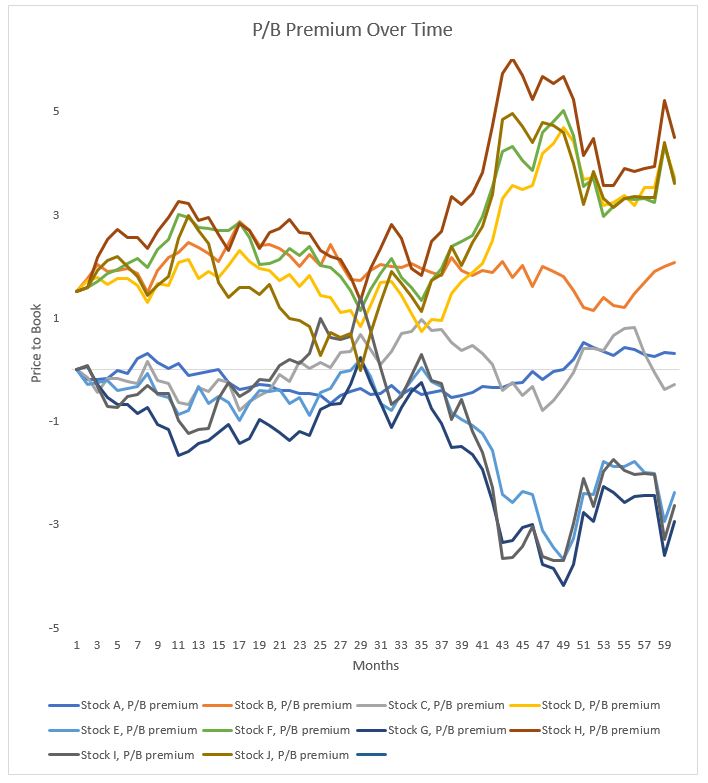

Check out the chart above. Imagine that the stock market was only made of two stocks, Stock A, and Stock B. Their P/B will change over time. At a given point in time, either the stock will be a value stock or a growth stock. A value investing strategy dictates buying any stock when it is deemed a value and selling it when that is no longer the case. When the P/B of Stock A is relatively low, buy it. When it is high, sell it. The same goes for Stock B. In this instance, the relativity is simply it’s P/B to the other stock (as opposed to the entire market).

(These are not real world P/Bs. This is just something mocked up in Excel using the Randbetween function.)

No matter what the P/B of either stock, there will always exist a P/B premium between the two stocks. Moreover, this premium will change over time as the P/B of the stocks change over time.

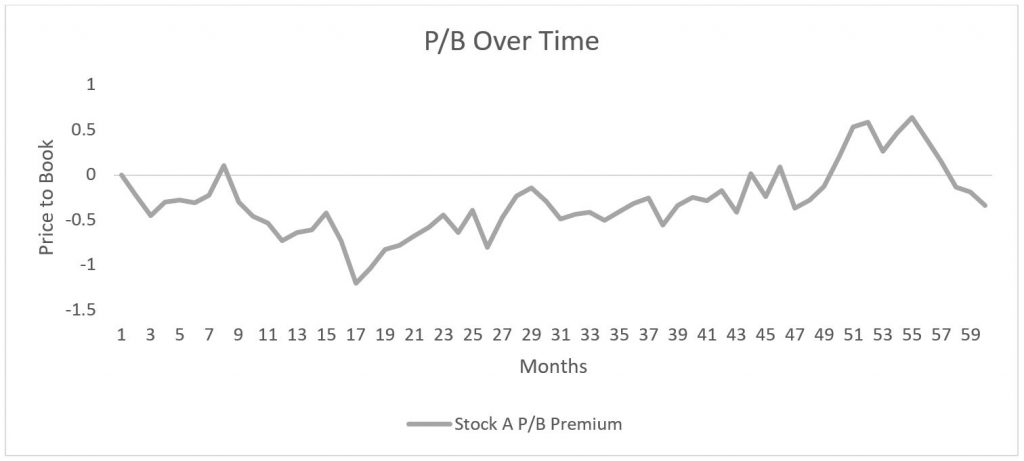

See the graph above. When a stock A’s P/B is above the market, that stock should be sold. When the stock’s P/B is below the market, that P/B should be bought. It’s a relatively simply strategy. But the point here is not so much to explain the value investing strategy so much to explain why (I think) the value premium will always exist.

Some stocks will always be selling a relatively higher P/B than other stocks. And since a company’s P/B changes over time, there will always be the opportunity to buy stocks with low P/Bs, wait until their P/B’s increase, and then sell them. Let’s expand this example to help the point.

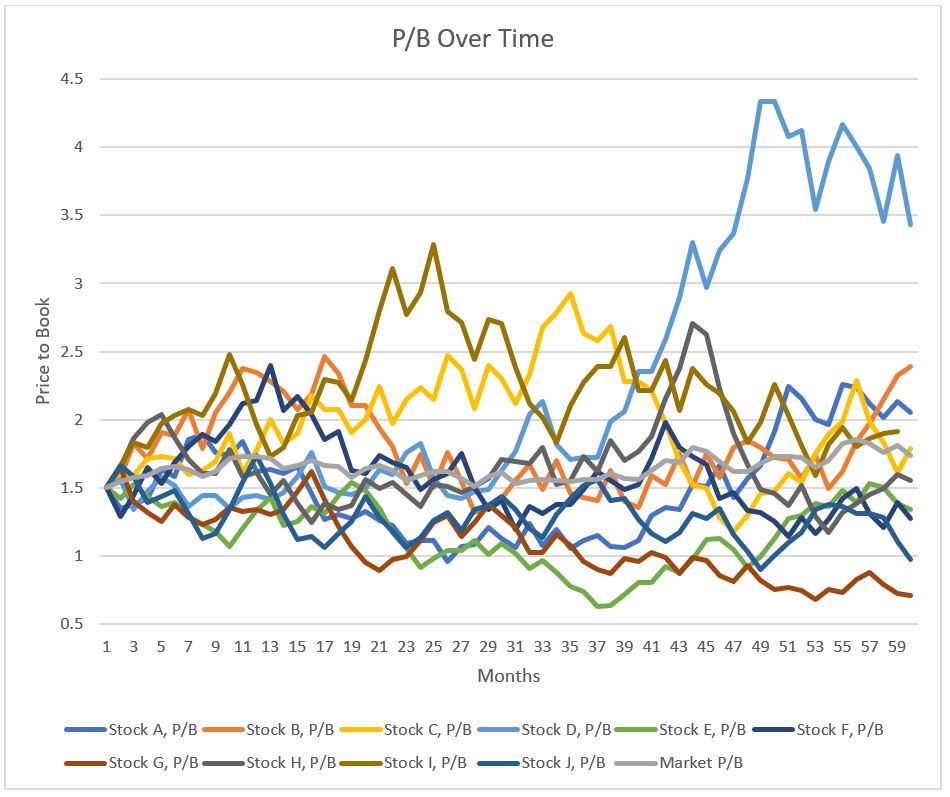

Imagine 10 stocks. All of their P/Bs fluctuate over time.

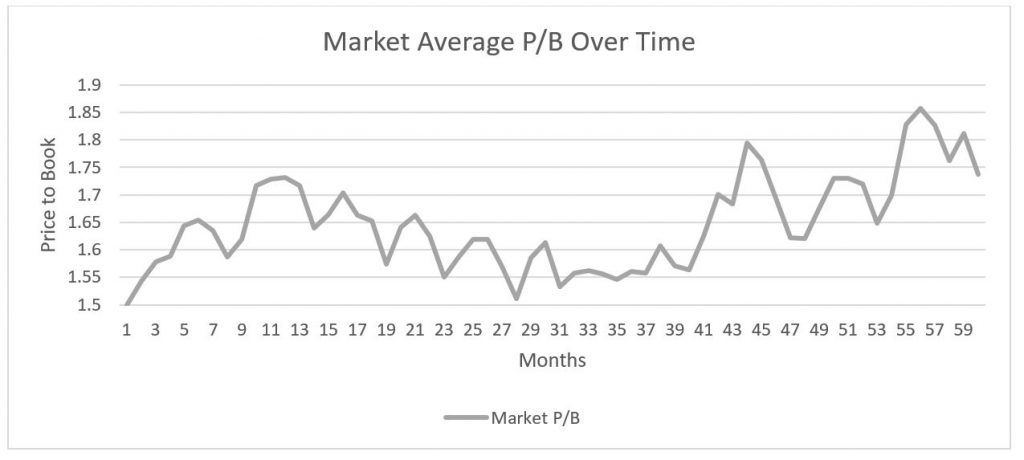

From these 10 stocks & their P/Bs, we can determine the market P/B at anyone point in time:

The market average P/B allows us to determine which stocks are selling at a premium or a discount relative to the market.

It is easy see here that there are multiple opportunities to buy companies that are selling below the market P/B and to sell those that are now above the market P/B (having once been below the market P/B.)

The math is simple and self-evident. The premise of mean reversion and the concept of relativity dictates that there will always be the opportunity to buy something being sold relatively cheaper and sell it once it’s price has appreciated.

Can Increased Competition Eliminate the Value Premium?

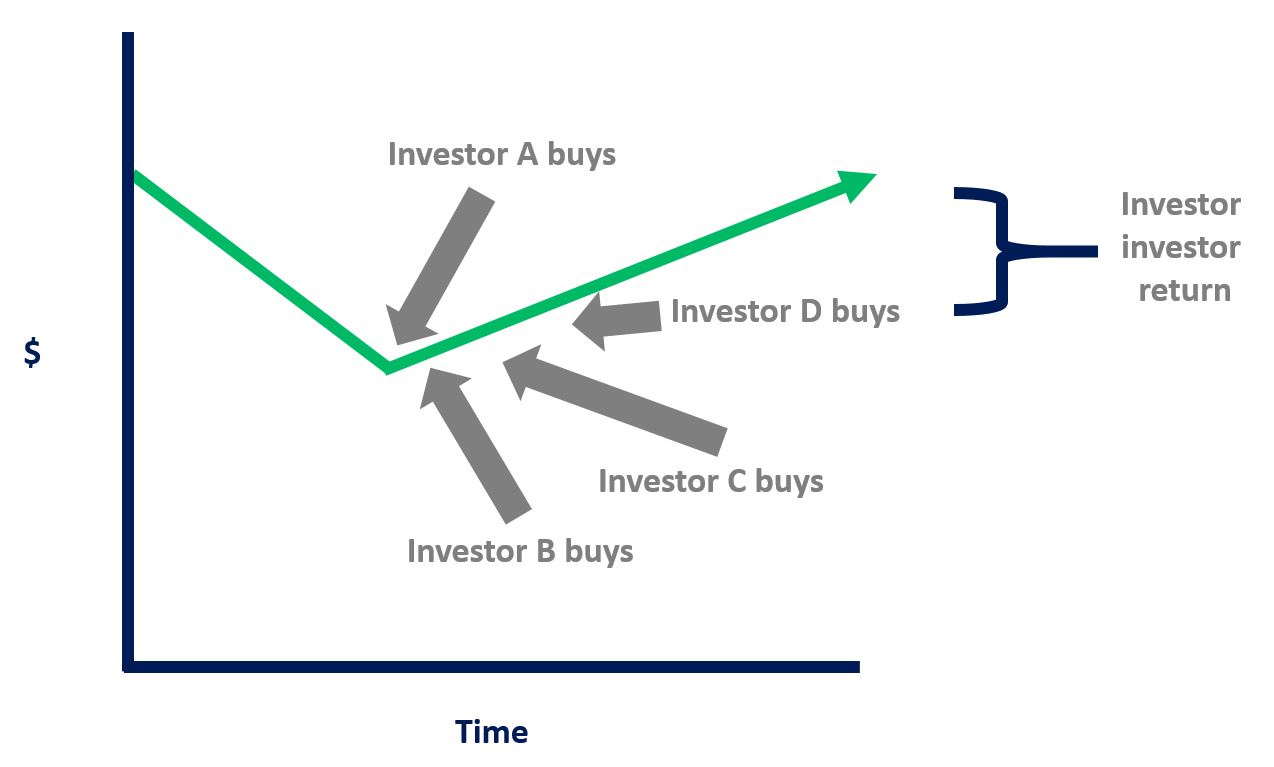

Theoretically, the value premium will always exist (if my assumptions are correct). However, increased competition may shrink the value premium. That is, if enough people are onto the premium, it can shrink. Why is that? Because too many people seeking out the premium can mean less deviation of valuations from the market average. Consider this illustration.

The stock of company A drops to as low as 0.95 P/B. Investor Joe sees that the stock of company A has dropped to such a low point. He buys it. Purchasing the stock marginally drives up its price. A higher purchase means less potential for price appreciation. Investor Sally, also a value investor, sees that the stock P/B of company A stock is selling at 1.0 P/B. Given that this is below the market average, she purchases the stock of company A. This marginally drives up the price. As more value investors purchase value stocks, it will drive up the price, ultimately increasing the P/B. Moreover, purchasing the stock not only drives up the price, but prevents the price from following lower.

While there will always be a value premium, increased competition can certainly shrink the value premium. If there is only one value investor in the whole world, that value investor will have many buying opportunities. With many investors shunning low-priced stocks, the price of an out-of-favor company can plummet. This means that one investors will enjoy a lot of (eventual) mean reversion.

Were there a million value investors, relatively lower-priced securities will be quickly snatched up. With more buyers driving up the price more quickly and more often, the investment return will be smaller.

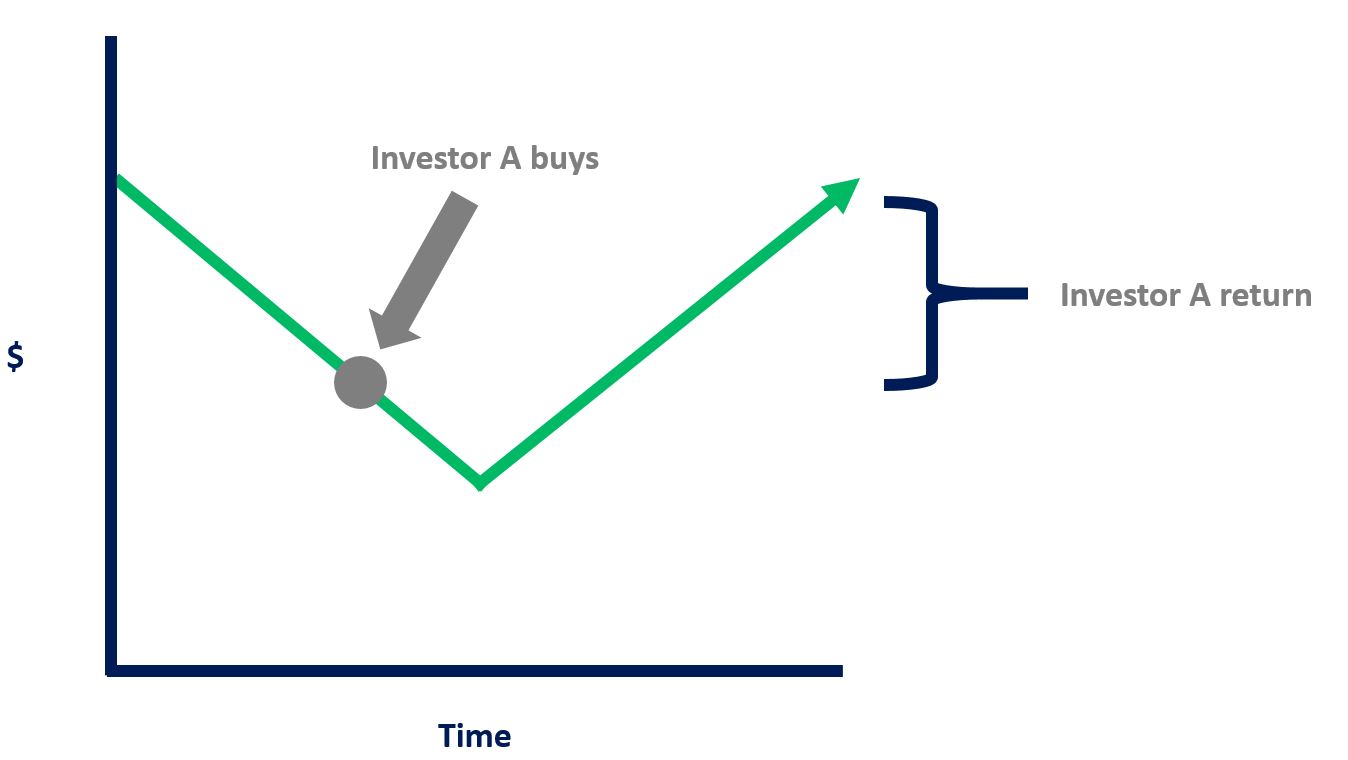

Let’s illustrate this. See the below illustration. Investor A is rewarded with a handsome investment return for being a value investor – buying what is out of favor and then waiting for the stock to become popular again. He is only the person doing this.

In this illustration, his purchase has no impact on the share price. However, in the real world, it might. There could be a price increase – which would depend on the amount of shares that investor A buys.

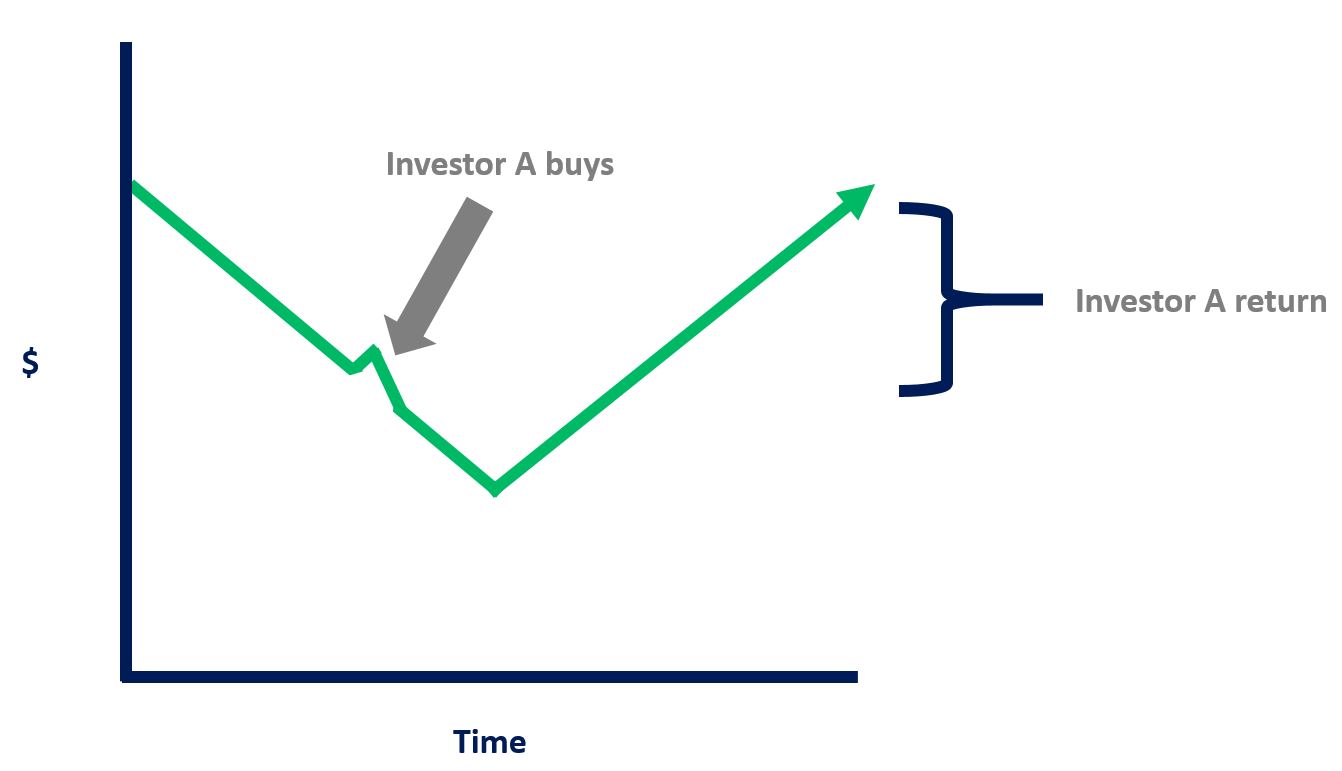

Now, if enough value investors are seeking out relatively lower-priced stocks, this will decrease the return available to value investors. Value investing will drive up the price of value stocks, decreasing the value premium. See the following illustration.

Costs

The value premium will always exist. Math simply dictates that. But, just because something works theoretically, it does not necessarily mean that it has a place in real world application. Why not? Costs.

Costs matter. There is a nearly infinite amount of literature on the subject. So, I will not bother delving into it. In short, while an investing idea may actually beat a given index (like hedge funds), it not may not beat that index after fees (just like hedge funds).

So, while the value premium will always exist given the math explained above, will the value premium be robust enough to warrant its implementation after fees. Of course not. If fees get high enough, no strategy is worth executing. If the fees surpass any excess return over the index available via the strategy, it makes no sense to implement. A strategy that fails that to beat the benchmark after fees makes no sense.

So, while the value investing should always work in theory, if the value premium shrinks over time to such an extent that the fees cannot justify the strategy, then we are better off index investing.

Leave a Reply