I’ve come across two distinct clients recently who were experiencing identical issues. Both clients were single women on the cusp of retirement. And, as with almost every middle-class American, these two distinct clients faced an identical situation:

They had not saved enough money.

The simple (obvious?) solution to their savings shortfall was to downgrade their lifestyle. The math behind this idea is relatively simple:

If you don’t have enough money at your current level of spending to get through retirement, spend less money.

For example, if you have a $1,000,000 and you expect to live 25 years, you can’t spend $60,000 a year. (Let’s ignore investment growth and inflation to keep this example simple.) In order to not run out of money, one must decrease spending to $40,000 each year.

However, for these two clients (and likely all humans), spending less money was simply an unimaginable impossibility. Neither of these two unrelated clients was willing to give up anything in their life. (Or perhaps more accurately, they refused to do the exercise of simply examining where their money was going.) And thus, every part of their spending was an essential need – from the multi-bedroom condo in West Los Angeles, to the rotating luxury automobiles.

Is that not strange? Why did these clients feel that these things (and all things they spent money on) were so essential? Why were they so unwilling to make any reductions to their lifestyle?

Earnings Trajectory and Inflation

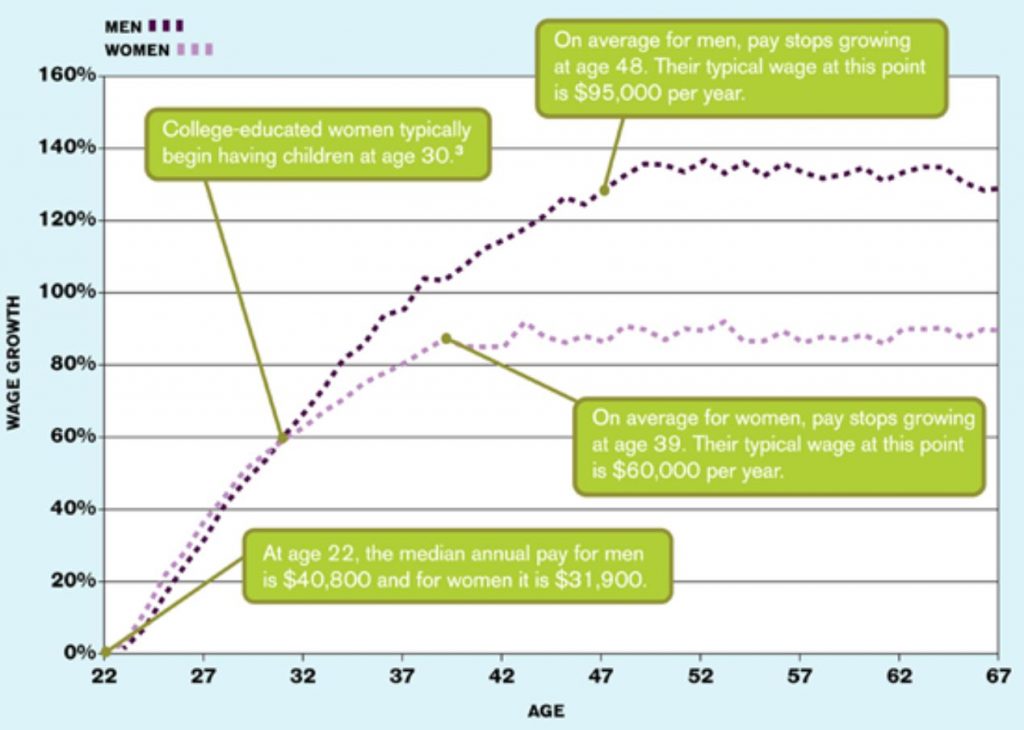

Given that both these clients were facing an identical scenario, I decided to find supporting evidence for my hunch (which I’ll get to in a moment). The info I sough was easy to find. Take a look at the following graph from PayScale.

On average, earnings peak well over a decade before retirement. What’s worse, the figures are nominal. This means that these figures do not account for the impact of inflation.

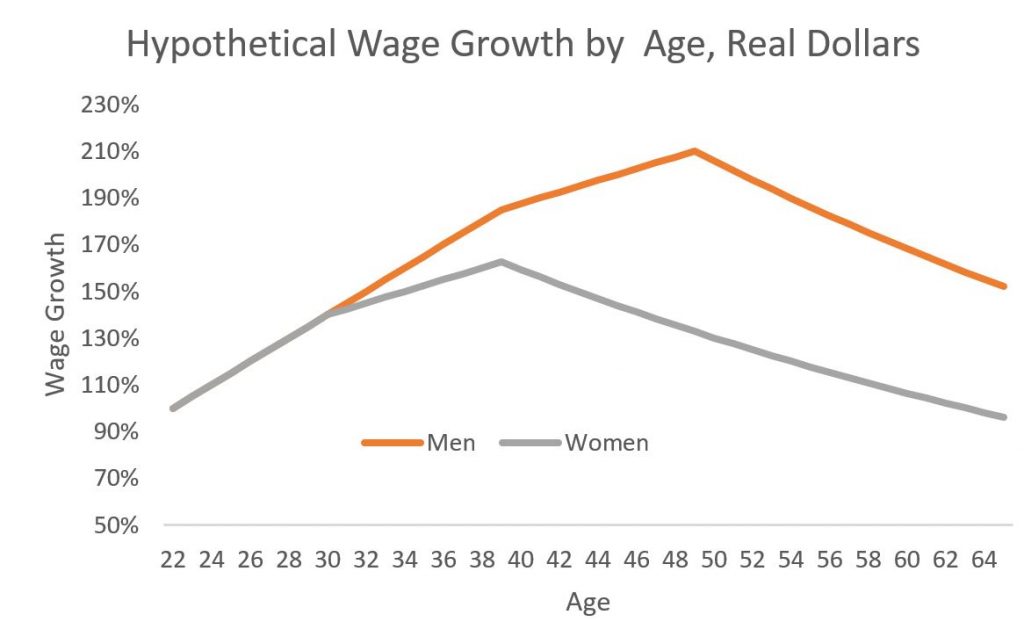

Incorporating inflation would transform the last decade of working years from a flat trajectory into a downward decline. See below for a rough approximation of what a lifetime earnings trajectory may look like when considering inflation.

Lifestyle Inflation, Earnings Trajectory, & Inflation

Let’s put this data to work into a hypothetical case study to showcase what is happening to American’s retirees.

American Jane graduates college. She gets a job. Next year, American Jane receives a raise in salary from her employer. At such, American Jane decides to treat herself. Maybe it’s a new car. Maybe it’s a fancy vacation. (God forbid she buys a timeshare.)

This happens every year; every year, American Jane gets a raise – and every year Americn Jane experiences in lifestyle creep. As Jane’s income goes up, so does her spending.

At age 39, (after 18 years of consecutive raises), American Jane is accustomed to a certain lifestyle. She drives a luxury car. She lives in a luxury apartment (or pays ever-increasing property taxes on her home purchase). She buys organic groceries, and she takes 5-star vacations every year.

Then something happens. At age 39, American Jane stops receiving raises. Her salary remains more or less the same for the rest of her life. That’s more than a decade of no wage growth! And remember, these are nominal dollars. Her salary stays the same before considering inflation.

Why does Jane experience no wage growth? Maybe this is because American Jane switches jobs to achieve a better work-life balance – or maybe because she’s laid off and replaced by someone younger. Her new job isn’t earning her any less money – but she’s not making any more money either.

Since her income isn’t going up, American Jane doesn’t further increase her lifestyle. (After all, she’s no dummy.) American Jane doesn’t upgrade to a full-size luxury model – although she continues to purchase (or lease) a new mid-size luxury model automobile every few years. She doesn’t take two luxury vacations a year – although she continues to take one luxury vacation annually. American Jane doesn’t hire a home chef – but she still continues to shop at Whole Foods.

American Jane’s income and lifetysle are fixed. Neither is growing.

But, her income isn’t truly fixed. It’s actually declining in real dollars.

- She’s paying more in property taxes (or rent) each year – because of inflation.

- Her grocery bill is growing – because of inflation.

- Her luxury mid-size car costs more today than the luxury mid-size car she bought five years ago – because of inflation.

American Jane is spending more dollars on her lifestyle each year, even though her lifestyle remains the same. This is because the same lifestyle costs more each and every year because of inflation.

Inflation & Stage Wage Growth on Late-Stage Earners

As financial planners, we worry about the impact of inflation on retirees. But as showcased above, it’s not just retirees who suffer from the impact of inflation. The financial plans of late-stage earners are also at great risk. They are at least two consequences of stagnant wage growth and inflation for late-stage earners.

Decreased or Negative Savings Rates

With a fixed income and increased spending (to maintain the same lifestyle), savings rate decline. Late-stage earners may even be eating into their savings to maintain their lifestyle.

As a financial planner, I have seen this one more than one occasion. Late-stage earning bankers and doctors raiding their brokerage accounts, and taking out HELOCs to pay for a home remodel, a child’s education, or a new car.

Lifestyle Expectations and Spending Inflexibility

The second consequence of stagnant wage growth and inflation is that the client has gotten used to a certain lifestyle. Maybe that means luxury apartments, luxury cars, and luxury vacations. In short, the client is accustomed to these luxuries; this is what the client expects.

Given the expectation for a certain standard of living, the client is not willing to decrease to their style – either because the client doesn’t understand the impact of inflation on a fixed salary, or doesn’t care. They want what they have and the won’t settle for anything less – the numbers be damned!

Working with Clients

Now that we know the problem of inflation on late-stage earners experiencing stagnant wage growth, how do we – as financial planners – solve this problem? Do we bother explaining to the client the impact of spending given stagnant wages and inflation? Good luck with that!

Humans are accustomed to a certain lifestyle (or rather they don’t handle change well). Therefore, it’s likely a hard sell getting client to tighten their belt after decades of them doing the opposite.

As financial planners, we know that the math is relatively simple. Pay now or pay later.

I think for those like American Jane, the game is over. It’s too late for them. How does one communicate to a client who has been driving a new Lexus for two decades that such spending is no longer an option?

Human: I want X.

Financial Planner: Then you need to do Y.

Human: I don’t want to do Y.

Financial Planner: Then you have to do Z.

Human: I don’t want to do Z.

Financial Planner: Then you don’t get X.

Human: I want X.

— Jon M. Luskin, CFP® (@JonLuskin) November 18, 2017

I don’t think you do. Instead, I think you impress upon your younger clients that they need to save more money now for the reason that not only will they earn nothing in retirement (to fund their living expenses), but that clients will earn less money than they are today in the future over the course of their working career. As such, (younger) clients need to increase their savings even more so today because they may not be able to do so in the future.

So true…

I find the intransigence astonishing. Like many baby boomers my parents lived through the depression and preached saving and spending less than you earned. It always seemed essential to me to look at my expenses and my income every year of my working life. As you described I had no raises in real dollars for the last 10 years of my career, but that changed nothing. In fact I was even more diligent about saving because I wanted a certain level of spending in retirement. It just seems crazy to not be rational about spending and income.