This post posits that structured notes are a bad investment. Fortunately, I have an easy task ahead of me. Why so easy? Because the reason that structured notes are a poor investment is obvious – and easy to understand. We don’t even have to look at any complicated math to understand why.

Banks Strive to Hide Costs

One commercial that keeps popping up on my YouTube feed is Chase’s “My Chase Plan.” With the “My Chase Plan,” consumers charge their credit card with a purchase and:

pay it off with no interest – just a fixed monthly fee

Sounds appealing, right? Who wouldn’t want to skip interest payments – but still buy what they want?

Yet there is a cost. It’s just that interest has been re-branded as a fee.

Financial companies consistently work to hide a given product’s costs – because no one likes to pay costs. And because the more salient a cost is, the more likely a consumer is to notice it, to object. Disguising costs, therefore, is the most lucrative play for the banks.

Costs are Bad for the Investor

Burying the costs of structured notes needs doing because any Boglehead will tell you that costs are bad for the investor. You don’t have to read the numerous studies on the subject to understand why: all else being equal, the more you pay, the less you get to keep for yourself.

For the confused consumers and advisors using structured notes, the costs of structured notes are far more complex. (And that’s the point!)

So, what are the costs of a structured note? Is it a sales load? Is it the underlying fund expense ratio? A structured note’s costs stem from the spread between the note’s underlying index and what the investor gets to keep.

The House Always Wins

We don’t have to go into any complex math to understand why the costs of structured notes are not a good deal for investors. All we have to do is understand a gambler’s luck.

Isn’t it great catching up with old friends? I had the chance to do this recently – over a BBQ’d lunch. While wolfing down baby back ribs, my buddy and I chatted. In addition to the usual banter about the well-being of the wife and kids, I asked my long-time comrade about his sports gambling hobby. His answer was assuringly mature. He confided:

You know, Jon, sometimes, I win. But, if you do it enough, on average, you lose.

Except for his choice of company, my friend is no dummy; he was smart enough to know what was happening to his wallet. Even the endorphin rush of the occasional win wasn’t enough to blind him to the simple math of the matter: gambling is a loser’s game.

The Odds of a Wager

But, why? Why can’t you make money gambling? After all, if you make a winning bet, you’ll be in the black. Just making enough winning bets, and you’ll come out ahead. Right? Not so. The problem is that the odds are stacked against you.

Imagine if I wagered on a coin toss with my buddy, the sports gambler. With a coin toss, the odds are 1:1, or +100 for calling “heads” correctly. In this instance, I win an amount equal to my bet – if my bet proves correct.

This means that if I bet on “heads” again and again, I’ll break even: I’ll win just as often as I lose – collecting just as much as I pay out. With enough coin tosses, my friend and I part ways with the same amount of money that we started with.

Now, imagine if I bet on a coin toss at a casino – and not against my friend. At a casino, I can’t get a +100 odds. Instead, the casino may offer odds of +90. So, were I to win a coin toss, I’d collect $90 – in addition to getting back my original $100. And if I lose, I’d lose my original $100 wager. This isn’t as good a deal as when I gambled against my buddy.

If I make this bet at +90 odds enough times, I’m going to walk away with less money than when I started. And since the casino makes this bet multiple times to multiple people, the casino comes out ahead.

As mentioned, the odds offered by the casino aren’t very fair. If there’s a 50/50 chance I can win a bet, theoretically, the odds (pay out if I win) should reflect that. This means I should be able to double my money – and not just increase it by 90%.

But, the unfairness is the point. That’s the odds you get when you make a bet with a business in the business of setting the odds (a casino, insurance company, etc.). The casino sets the odds so that the casino will come out ahead of the gambler – on average. If the casino didn’t set the odds that way, the casino wouldn’t be in business for long.

That’s not to say that you can’t win the occasional bet. You most certainly can. But, you will not come out ahead on average. Just as my friend learned from experience: if you bet enough, you’ll walk away with less money than when you started. That’s inevitable, given how the odds are set.

Insurance Odds Not in Your Favor

The casino collects more in bets than it pays out in winnings. Insurance works the same way: the insurance company stays in business by collecting more insurance premiums than it pays out in insurance benefits. Doing so ensures the long-term profitability of the insurance company. (This is why it may make sense to self-insure if you can afford to.)

To be clear, it doesn’t matter what you’re insuring (your life, your car, etc.) – or how much the insurance costs. Odds are, you’re going to pay more in insurance premiums than you will ever collect in insurance benefits.

Pretty simple idea, right? Intricate math is not needed to understand the concept: for casinos and insurance companies to exist, they must profit. That profit comes from the user of their products losing bets – on average. If you’re taking someone else’s odds, you are likely going to lose. This applies to gambling, insurance, and all kinds of financial products – like structured notes.

Structured Notes

A structured note is an investment wrapper that can act like an indexed annuity: investors surrender a portion of their investment return in exchange for downside protection. Investment performance is tied to an index.

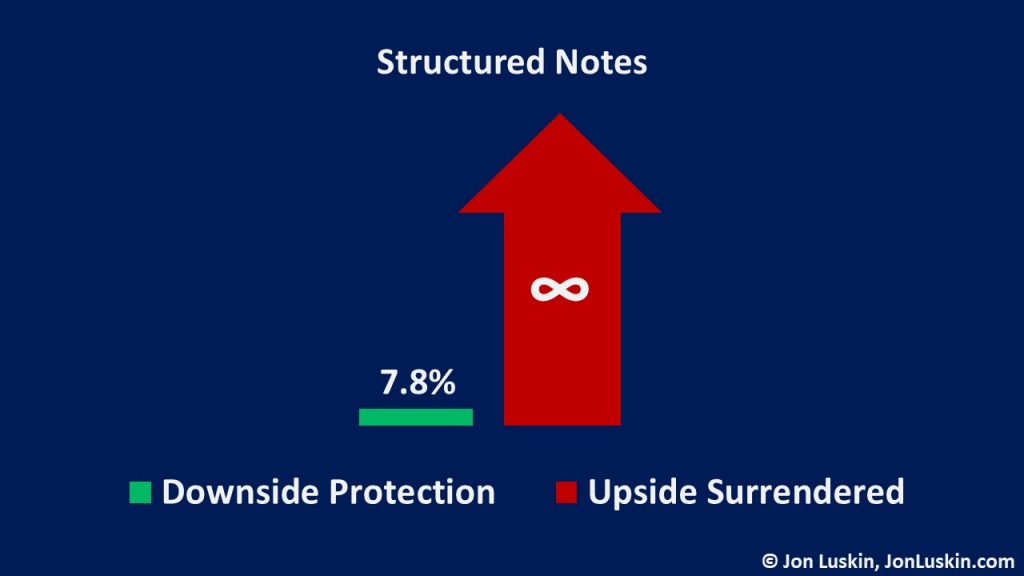

To borrow Investopedia’s illustration of how a structured note may work: the structured note eats the first 7.8% (10% before surrendering dividends) of any investment loss. In exchange, investors surrender dividends and any gains above 24%.

Refer to the graphic, where the numbers of this particular structured noted are laid out in a visual format. In exchange for less than 8% of downside protection, investors give up a theoretically infinite investment return (anything above 24%).

Of course, the difference between best/worst-case scenarios (saving 7.8% versus losing an infinite amount of gains) is exaggerated. Because no one is going to earn an infinite investment return. In reality, an investor is going to surrender some amount less than infinity. But, on average – investors lose more in gains surrendered than they gain in downside protection. Because if they didn’t, no banks would be willing to sell structured notes.

Should I Use Structured Notes?

If using structured notes is effectively gambling with odds not in your favor, what makes more sense?

- Play a game where – on average – you lose.

- Don’t play the game.

Warren Buffett famously said that when ‘dumb’ money acknowledges its limitations, it ceases to be dumb. Buffett was talking about index investing. But, this applies perfectly to structured notes too.

Complexity Signals a Fleecing

But, don’t take my word for it. Evidenced-based investing advocate Larry Swedroe makes the case that the staff at Wells Fargo and other banks are charged with raising capital. If those banks can raise capital more cheaply (by selling elaborate financial products), why wouldn’t they? (They do!)

Portfolio Insurance without Structured Notes

So, now we’ve established that structured notes aren’t a good deal; their insurance of limited downside protection isn’t worth the cost of foregoing dividends and giving up excess gains.

But, Jon, how do I protect my client’s portfolios from market drawdowns – if not without a buffer from structured notes?

That’s quite an easy question to answer: hold (more) high-quality bonds. If you’re not using United States Treasuries for a portfolio’s fixed-income allocation, do so. And if you are already doing just that, then increase your fixed-income weighting (at the expense of your equity allocation).

In short, if you’re taking too much risk in a given portfolio, the solution is not to implement an overly-complex piece of financial wizardry (i.e., buy a structured note, indexed annuity, or other such nonsense). Don’t buy over-priced insurance. Instead, take less risk.

If that sounds boring, you’re right. But boring, commonsense approaches is what works in investing and personal finance.

So, what do you think? Do you use structured notes in client portfolios? If so, why?

Hi Jon,

I’ve used structured notes and market link CD’s for years. The CD’s have been excellent bond alternatives. You mention holding more high quality bonds. How is that a good investment when the 10 year performance of IEF is .73%. Basically losing money after inflation. Structured notes can be an excellent addition to a portfolio.