A few weeks ago, I was at a local early retirement (FIRE) meetup. The group was gracious enough to let me rehearse a presentation on bonds that I will be giving to a group of financial advisors.

After my presentation, a gentleman in the audience raised his hand. He said he was targeting early retirement. Yet, he was sitting on a 100% stock portfolio. The recent market losses of (at the time) ~20% had thrown a wrench in his FIRE plans. What should he do now? he wondered.

Table of Contents

Why Is Everyone Taking Too Much Risk?

This isn’t uncommon; even those at conventional retirement ages (~65) are moving into retirement with relatively aggressive portfolios. How did we get here? Recent stock market performance.

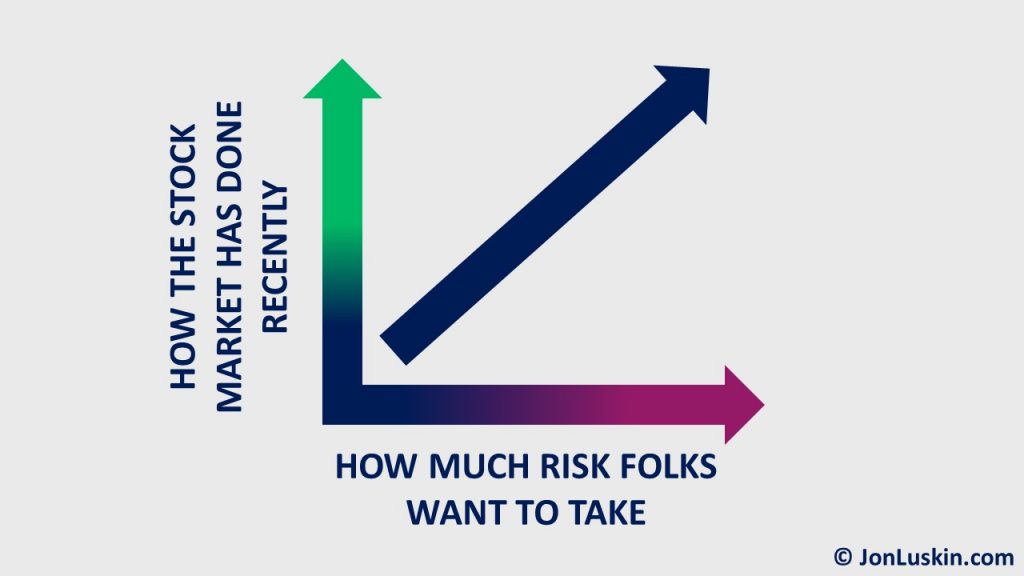

For the most part, markets have done quite well since the bottom of the financial crisis (March 9, 2009). When markets do well, folks can hardly help themselves from taking more risk. That means investing more – or all – of their portfolio in stocks. In short, many younger investors – and even those with more life experience – may be holding a portfolio that’s too aggressive given their personal goals.

The behavioral finance term for what investors are experiencing is recency bias. The market has done well. So, people assume (perhaps incorrectly) that the market will continue doing well.

Yet, that’s not how investing works; tomorrow’s stock market performance is largely random compared to the day before. In the long term, of course, the market has gone up. But, predicting the market’s performance even over the next few years is difficult.

Another behavioral finance term describes what investors are doing: performance chasing. Stocks have gone up; people want a piece of the action. So, they pour more money into stocks.

(Of course, performance chasing isn’t exclusive to stocks. You’ll find it in cryptocurrency and all the alternative assets that investors flock to after those investments have done well.)

Why Managing Inve>Why Managing Investment Risk in Retirement Makes Sense

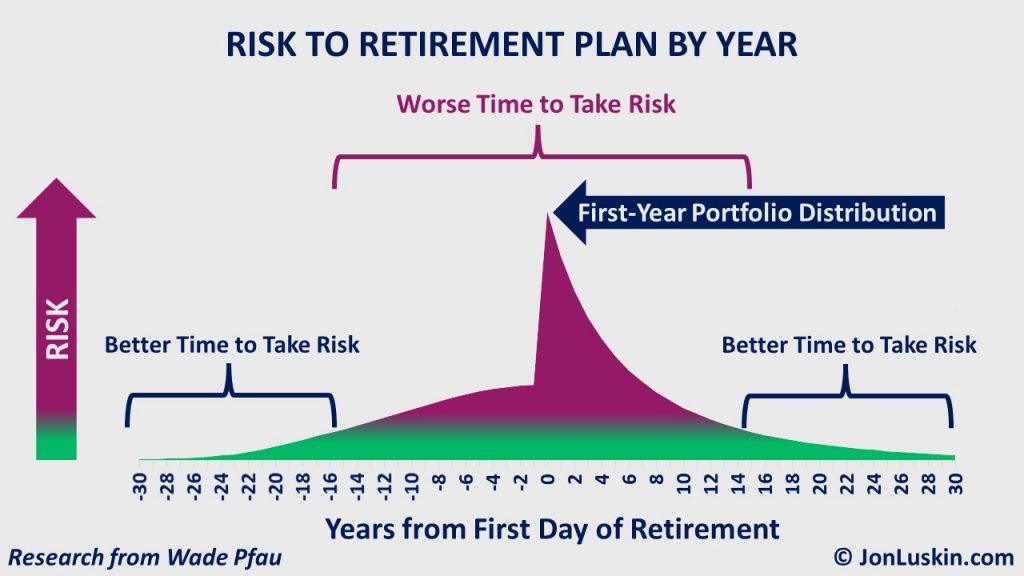

sing on risk at the outset of retirement so important? Because the first year of retirement is the riskiest. That’s the case whether you’re targeting retirement at 65 or are retiring earlier.

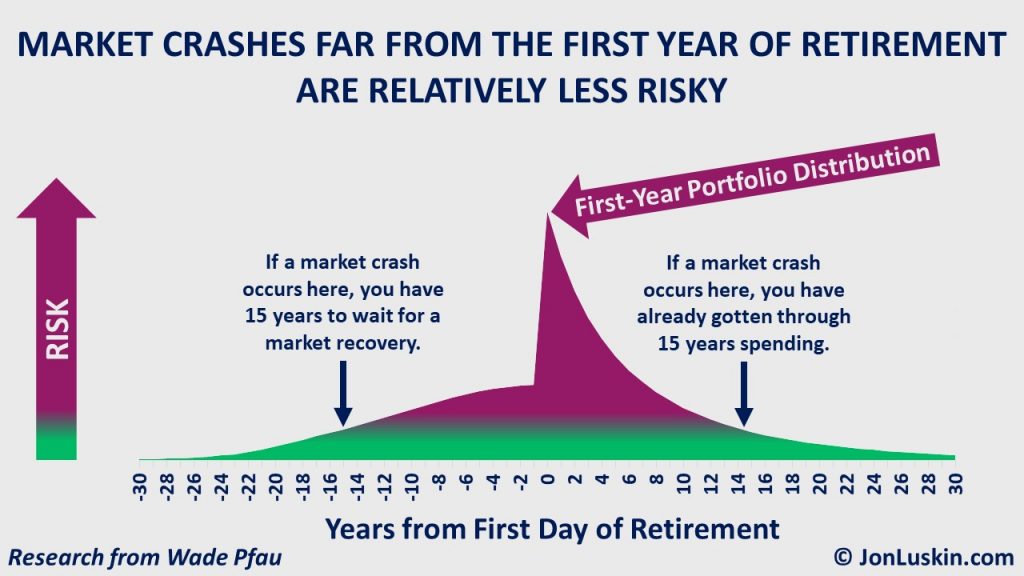

Selling at a market bottom – at the beginning of retirement – severely impacts the success of a retirement plan. That’s much more detrimental than selling at a bottom 15 years before retirement, or even 15 years into retirement.

If you’re 15 years out from retiring (and are therefore still far away from taking money out of your portfolio), you have time for your investments to recover. If you’re 15 years into retirement, you’ve already gotten through 15 years of spending; you no longer need your portfolio to last as long.

The nerdy term for the first-year-of-retirement-is-the-riskiest-year is sequence risk. Those looking to learn more can read chapter 2 of Wade Pfau’s Retirement Planning Guidebook.

In short, being risky at the outset of retirement has significant consequences. This suggests that (near) retirees be relatively conservative with their portfolio at the outset of retirement; you can always take more risk later.

Unfortunately for retirees of all ages, we can’t go back in time and opt for a more conservative portfolio knowing that poor market performance was coming. This is why it’s critical to ensure that your portfolio reflects your risk tolerance ahead of time.

Should You Take Investment Risk?

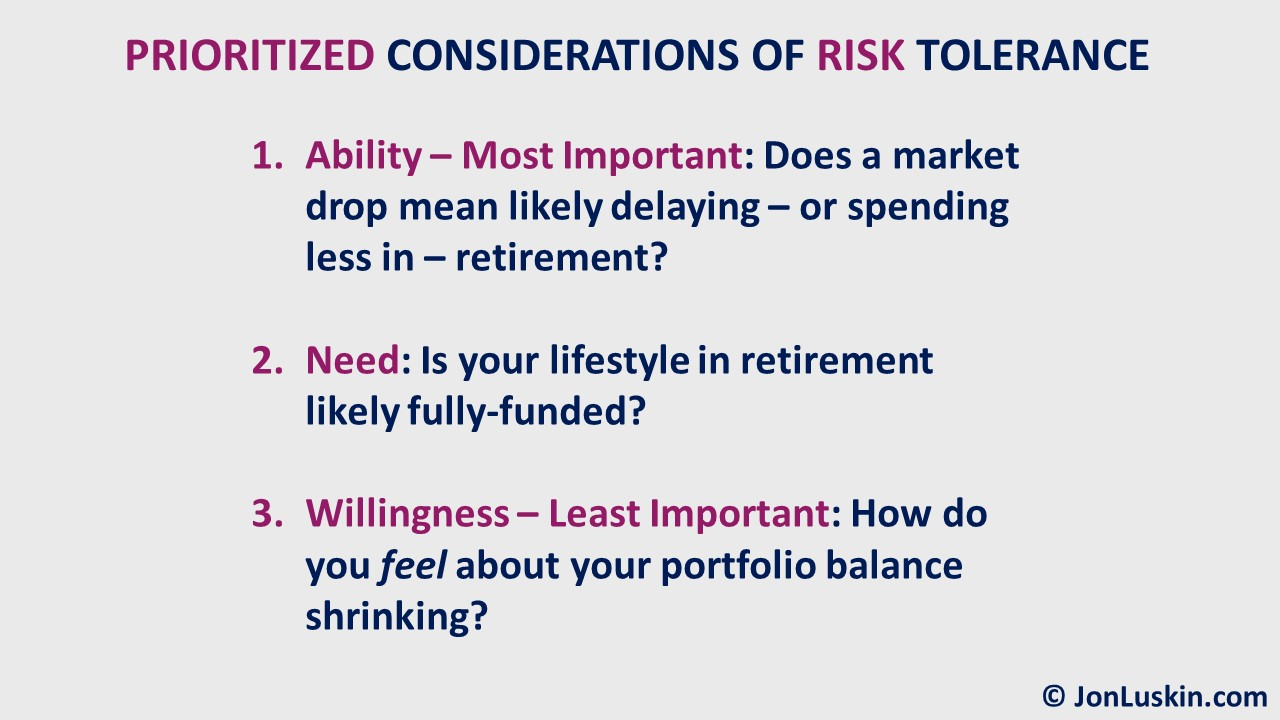

>Should You Take Investment Risk? Answer Man podcast evaluates risk tolerance on three different levels. Let’s use that approach to evaluate how both conventional and early retirees can determine their risk tolerance.

How Well the FIRE Community Manages Inv>How Well the FIRE Community Manages Investment Risk

l of risk tolerance lines up. Consider the gentleman I introduced at the beginning of this blog post. He only thought about his willingness to take risk. (He wanted to invest aggressively.) He did not consider his need nor ability for risk.And, given his question about investing amidst a market correction, we can infer that he underestimated his ability to take risk – given an inflexible retirement plan. (That’s quite common – and why I’m writing this post!) Moreover, assuming he was on track to retire shortly (i.e., his retirement was fully funded given the size of his portfolio), he likely also underestimated his need to take risk.

Separating Willingness to Take Risk from Need and Ability

This problem is that most folks – especially the FIRE community – consider only their willingness to take risk. As instructed by JL Collins’s The Simple Path to Wealth, they will invest 100% of their money into Vanguard’s Total Market Index Fund (VTSAX), an all-stock (relatively risky) portfolio. (And for the FIRE community, that usually isn’t a problem. For this crowd, ability and willingness tend to go hand in hand.)

Ability to Take Risk

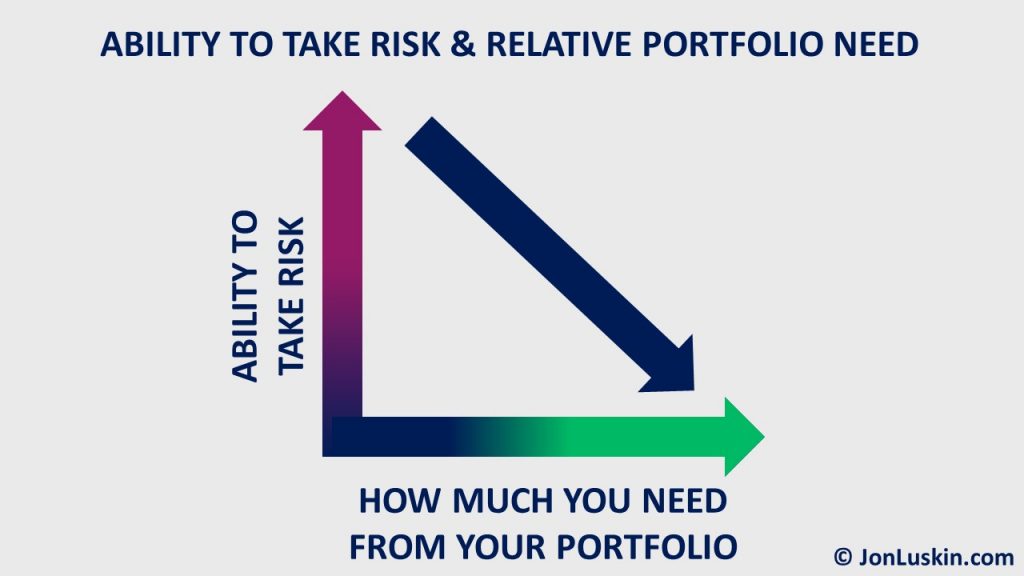

One’s ability to take risk depends upon the flexibility of their retirement plan. The more flexibility one has with spending (decreasing if need be), the more flexible one is with their retirement date, and the more passive income streams they have (rental property, pension, annuities, etc.), the more aggressive they can afford to be with their investment portfolio. The opposite also applies; if one’s spending is inflexible and so is their retirement date, that suggests the need to be more conservative with investments.

Limited flexibility can be self-imposed. That could be the case with FIRE folks. (Think, “I have to retire at 45. I can’t stand working!”). Or, the lack of flexibility can be the result of life circumstances. (“I have to retire at 60 because no one wants to hire a computer programmer that old.”)

Need to Take Risk

The need to take risk, however, is deeply personal. It will depend on one’s intended lifestyle in retirement compared to savings to date. Is your retirement lifestyle fully-funded? Or, does your portfolio still need to grow in order to spend at the level you envision for retirement?

How Well Conventional Retirees Manage Investment Ri>How Well Conventional Retirees Manage Investment Risk

need to make multiple considerations in determining their risk tolerance: not just their willingness to take risk, but also their need to take risk and, most importantly, their ability.Unlike early retirees, those at traditional retirement ages – who will depend upon their portfolio to fund their living expenses – have less ability to take risk. All else being equal, that suggests being more conservative with their investments.

In assessing their own risk tolerance, traditional retirees will likely find that they have fewer options – less flexibility – for managing risk. For example, some are forced into retirement – as with the 60-year-old computer programmer above. Or, they may be forced into retirement from poor health.

Willingness to Take Risk Should Be Checked by Ability t>Willingness to Take Risk Should Be Checked by Ability to Take Risk

ved, are either about to retire, or at least just fully funded for retirement – and still have an aggressively invested portfolio. At that point, there’s little to gain compared to much more to lose. Legendary Boglehead® Dr. Bill Bernstein says it best:If you’ve won the game, stop playing.

Said differently, investors need to understand that willingness to take risk can come into conflict with – and be an almost irrelevant consideration compared to – ability and need to take risk; one’s ability to take risk should be the primary limiting factor for risk tolerance when investing. Regardless of their willingness to take risk, one – generally – should only take as much risk as they have the ability to bear.

When Investing Aggresivley in Retirement is Reasonable

The only scenario I can think of where any retiree – be it conventional or early – could enter retirement with an aggressive portfolio is if they’re already fully funded – if they have more money than they could possibly need in retirement, and then some. At that point, they’re investing for legacy – to leave a larger sum behind for family and/or charity.

For example, an octogenarian scheduled a One-Day Financial Review for later this month. With annual expenses of ~$400,000, his spending is significant. However, that spending is small relative to his net worth of ~$50,000,000. Given such a small distribution rate and relatively shorter investment timeline, a 100% stock portfolio – for him – isn’t unreasonable.

As with the example above, one will have to consider their personal circumstances: how much of their portfolio do they need to fund their lifestyle in retirement?

How to Manage Investment Risk

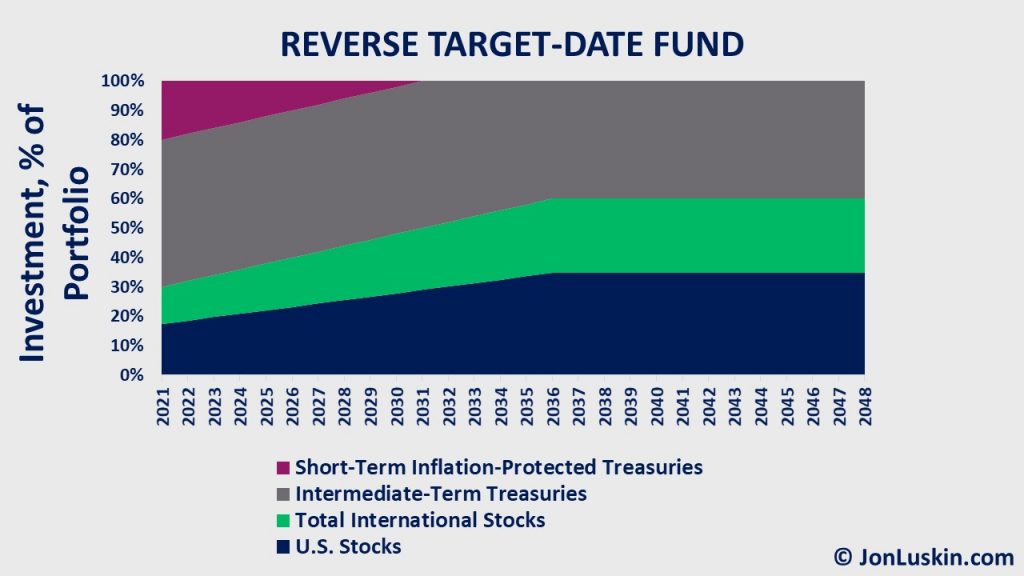

For those not relying on>How to Manage Investment Riskpenses in the near term, investment risk is managed by having a long time. (The exception being those with more money than they could ever spend – as with the example of the ~80-year-old gentlemen just mentioned.)

With enough time, any poor market performance can be waited out. At least, that’s how it’s worked in the past. (Past performance is not a guarantee of future returns.)

Conventional retirees don’t have the luxury of time. (And for that matter, neither do early retirees if they’re inflexible about the early part. Said differently, an early retiree who is inflexible with their retirement probably has less ability to take risk.)

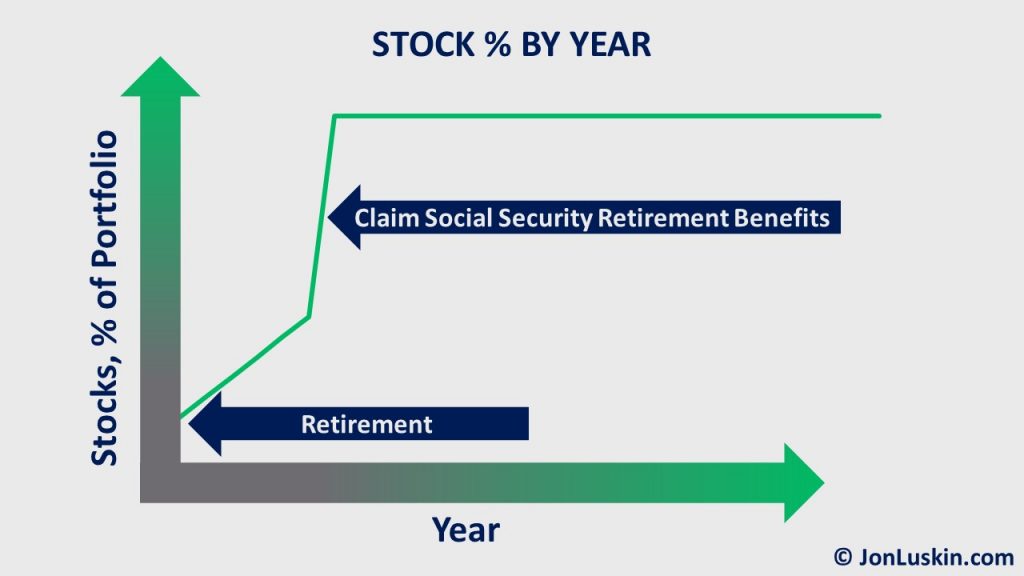

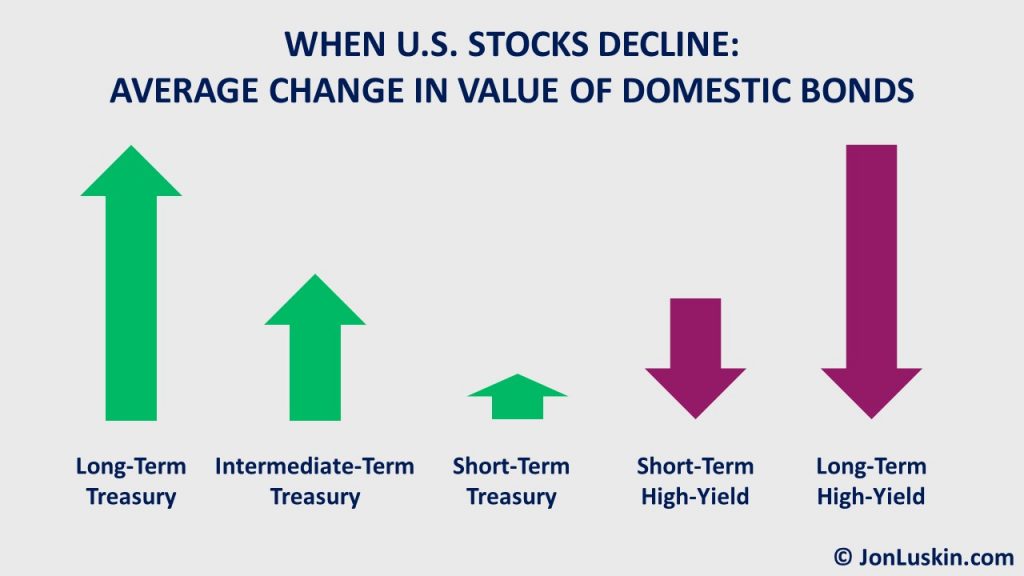

Those without time on their side must pick another option for managing risk. Frequently, that means investing more conservatively using a relatively safer, shorter-term investment. Generally, that’s going to be cash and/or high-quality bonds. (Compared to cash, high-quality bonds may offer a higher sustainable distribution rate in retirement, in part because of their low correlation to stocks.)

Complex Strategies for Managing Investment Risk

Beyond the scope of this post are other (more elaborate) risk management strategies, including dynamic portfolios, decreasing a stock allocation as an investor moves through retirement. Investment risk can also be managed by annuitizing a portion of their portfolio (which also helps manage longevity risk: living too long). There’s also the strategy of accessing buffer assets: borrowing from an existing cash-value life insurance policy or home equity during market corrections, paying that debt back after a market recovery.

Lastly, other risk management strategies include:

- being flexible with spending

- generating some income in retirement

The Optimal Stock/Bond Mix for Retirees

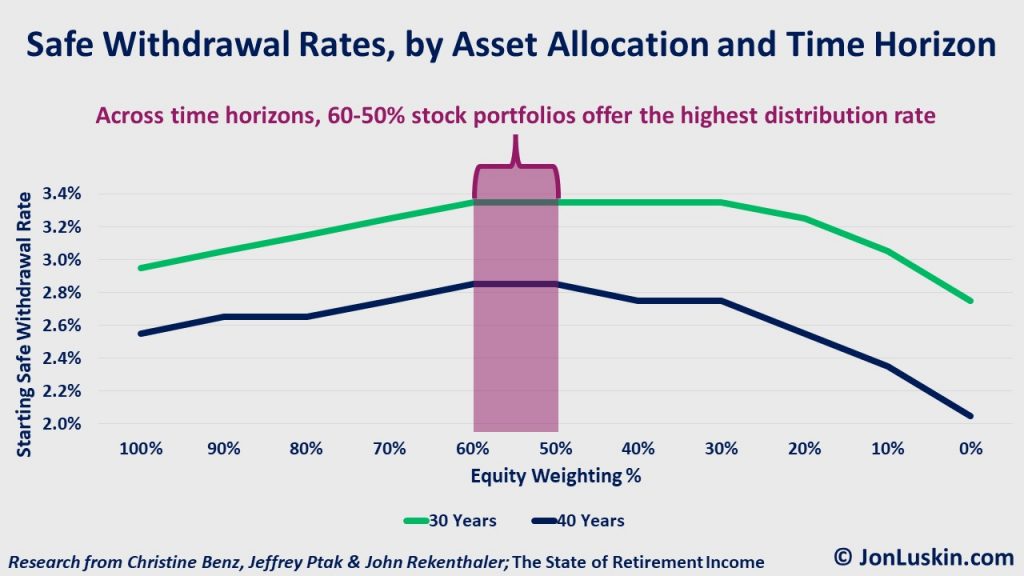

Research frequently shows that the >The Optimal Stock/Bond Mix for Retireesic) stock/bond mix is 50% to 60% stocks and the rest in bonds. For retirees aiming to deplete their portfolio at the end of 30-40 years, that stock/bond mix gives them the best odds of success.

Not All Portfolios Are Created Equal

One important caveat: The above considers one’s stock/bond mix as a way to measure the risk of the portfolio. Yet, there’s a huge difference between a portfolio of low-cost, globally diversified index funds and a portfolio of individual stock picks. Even if you’re sitting on a mix of 60% stocks and 40% bonds – but those stocks are a handful of tech stocks – that’s still quite risky. At least, that’s the case compared to a similar 60/40 that uses broadly-diversified, low-cost funds.

Managing Risk (Likely) Means Earning Lower Investment Returns

As with much of financial p>Managing Risk (Likely) Means Earning Lower Investment Returnsse worst cases, we better manage risk. That way, even if that worst case does show up, we’ll be better prepared.

Ideally, the worst case won’t happen. If so, we may have invested our portfolio too conservatively (missing out on higher investment returns). Yet, that doesn’t mean that being more conservative in our planning was the wrong decision; it means you weren’t unlucky.

That’s the basics of managing risk. Yet, for many reading this post, that information may be coming too late. That begs the question:

What now? What do I do if I’ve taken too much risk with my portfolio right before retirement?

What to Do If You’ve Taken Too Much Investment Risk

Whether you’re an early retiree or a convention>What to Do If You’ve Taken Too Much Investment Risk of your portfolio in stocks. With the recent market drop, you’ve got to manage the consequences. What should you do? Let’s consider the options for both conventional and early retirement.

Early Retirees

With time on their side, early retirees have more flexibility (as already covered) with what t>Early Retirees/p>

#1. Postpone Retirement

For a would-be early retiree, a valid (though somewhat unsatisfying) solution is to keep working. This approach gives a portfolio time to recover. Moreover, by continuing to work, one can invest at decreased market prices. If this is you, consider yourself lucky to have this option.

#2. Retire anyway, but spend less in retirement (at least initially)

If working isn’t one’s jam (understandable, since we’re talking about early retirement), there’s the option to retire anyway. At that point, the best tool for managing risk is spending less – at least until one’s investment portfolio has had time to recover.

How to Invest Once You’ve Taken Too Much Risk

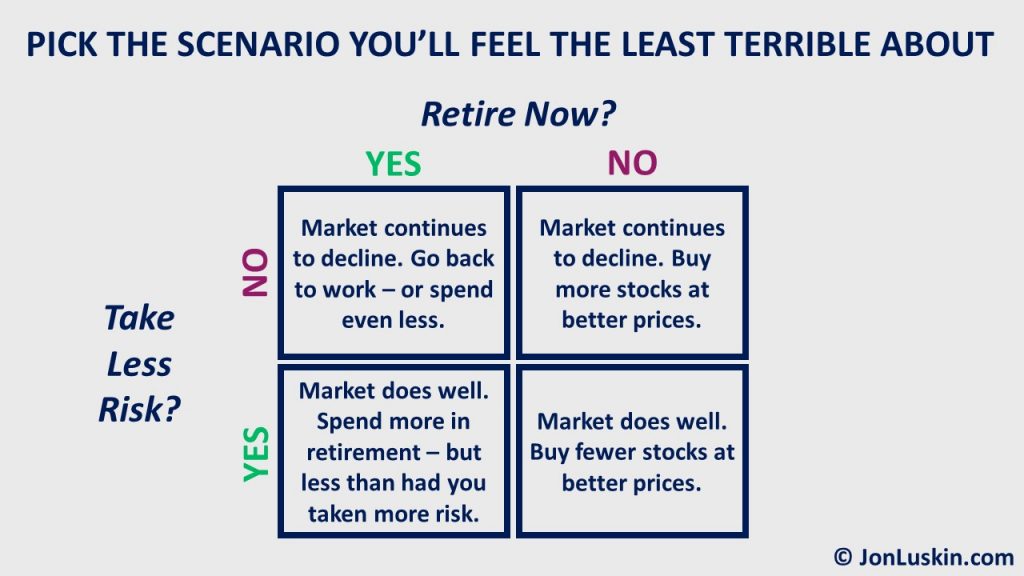

Yet, separate from the decision to retire or keep working, one will have to decide how to invest going forward. Should you take less risk now? In making decisions, consider the worst outcome for each approach. Pick the approach that gives the least terrible outcome.

Those aggressively invested targeting early retirement will need to decide whether retiring now still makes sense. They’ll also have to decide whether or not to take less risk.

If the handy matrix above can’t help you decide how to invest, consider the exercise in the final section.

Conventional Retirees

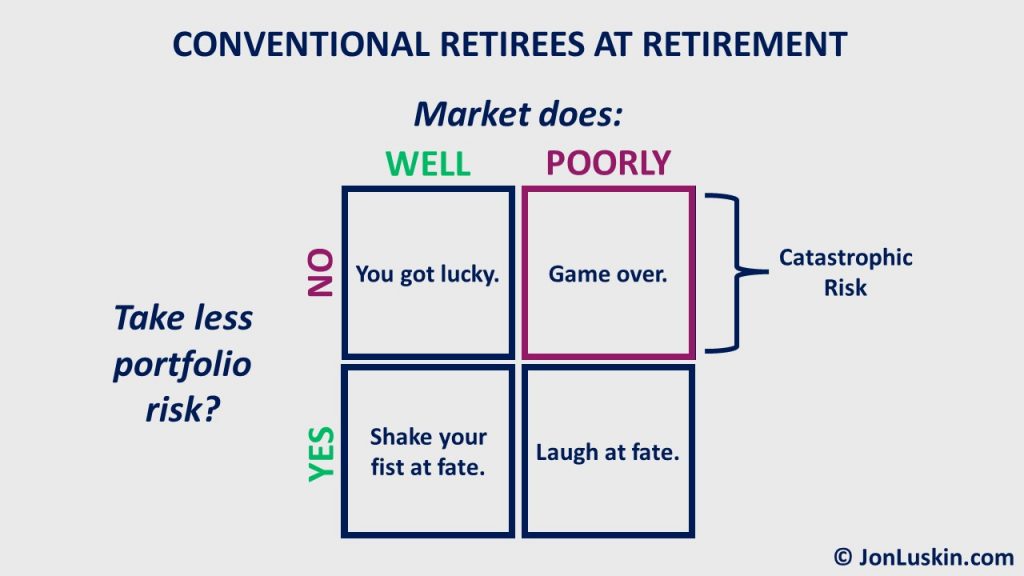

For the conventional retiree who’s approaching retirement and has already suffered losses from being too >Conventional Retireesroach is to move to a more conservative portfolio immediately to curtail any further losses. The catch is that the market could recover from here on out. (And it appears it has already started to, with U.S. stocks off their mid-June low.)

That means some unfortunate market timing on the part of the near-retiree. But this is not as unfortunate as the opposite scenario: taking too much risk, only to have your portfolio further decrease in value. That’s the absolute worst case.

As we already mentioned, planning around those worst cases can protect us from the most extreme risks. (Yet, that’s not necessarily the approach that will create the greatest wealth.)

As with the exercise for early retirees, evaluating the worst case can help would-be retirees make the decision that’s best for them. What would they feel worse about:

- Moving a portion of their wealth to bonds, only to see the stock market rally, or

- Leaving their portfolio invested aggressively, only to witness further market declines?

Assuming you’ll have enough time to play catch-up, consider the situation you feel worse about. Then, choose the opposite.

Should I Move from Stocks to Bonds After I’ve Lost Money?

If you’re still having trouble deciding what to do, consider the following exer>Should I Move from Stocks to Bonds After I’ve Lost Money?topedia.com/terms/e/endowment-effect.asp#:~:text=The%20endowment%20effect%20refers%20to,irrationally%2C%20than%20its%20market%20value.">endowment bias (thinking what you already have is better simply because you have it) and the sunk cost fallacy (not changing from a losing strategy because you’ve already lost money).

- Look at the balance of your account value.

- Imagine – if instead of stocks, bonds, VTSAX, and everything else – you had that balance in cash.

- How would you invest that cash?

If that answer isn’t the exact portfolio you have now, you’re likely not in the right portfolio. That means changing your portfolio to better reflect your tolerance for risk.

Disclaimer: For education and entertainment purposes only. Not specific investment advice. Confer with your tax and investment professionals before making any investment decisions.

How should one handle having too much risk in taxable accounts? Due to some stock market luck, I exceeded the assets needed for early retirement. I can’t quickly rebalance without taking a giant tax hit. But I’m kind of desperate to lower my risk here…

Greetings J,

Thanks for your question.

Without knowing about your personal circumstances, I can’t answer your specific question. The following is a general answer – that may or may not apply to you.

Generally, consider prioritizing investment decisions based on personal goals and not taxes. That is, we should strive to get our investments right first, so that our investments reflect what we are looking to accomplish. Then, if we can accomplish our investment goals more tax-efficiently, it makes sense to take advantage of those tax planning opportunities.

For example, if given a chance to invest in a low-cost stock fund in either a taxable account or a Roth IRA, opting for the Roth IRA can make sense.

That is, we don’t want to let taxes dictate our investment strategy. That’s because you stand to lose a lot more holding inappropriate investments that don’t reflect your goals than you could ever save in taxes.

Investments first; taxes second.

Best wishes,

Jon

Hi Jon,

What has your approach been around fixed income in the last few years?

Hindsight would have said to go short duration until rates rise, but that was quite the wait for those doing so for the last decade or so.

Fearful of how rising rates can erode a portfolio with mid term bond funds, but don’t want to add the complexity of a ladder or individual bonds.

Love your stuff!

Eric

Greetings Eric,

Thanks for the kind words.

As you might imagine, I wrote a post about just that question:

https://jonluskin.com/six-investing-strategies-for-a-rising-interest-rate-environment/

Best,

Jon

Wow, what a great and timely post. After saving, investing and rebalancing like robots in a simple 3 index fund portfolio for decades we’re retiring at 56 with about 40x yearly spending and no debt. I just rebalanced to 50/50 from 60/40. It was surprisingly very hard. Rationally, I know we could possibly afford to take more risk and we’ll be earning less long term on our portfolio. Yet, knowing that our dividends alone will supply a bit over half of our yearly budget or more and 3 years in cash to start, along with a Treasury ladder and a high yielding short term treasury etf (sgov) I think I made the right choice. I hope so.

This article raises such a crucial point about balancing risk and regret for those nearing retirement. The “worst-case scenario” exercise is an excellent framework for decision-making. It’s interesting how it focuses not just on numbers but also on personal comfort and emotional resilience.