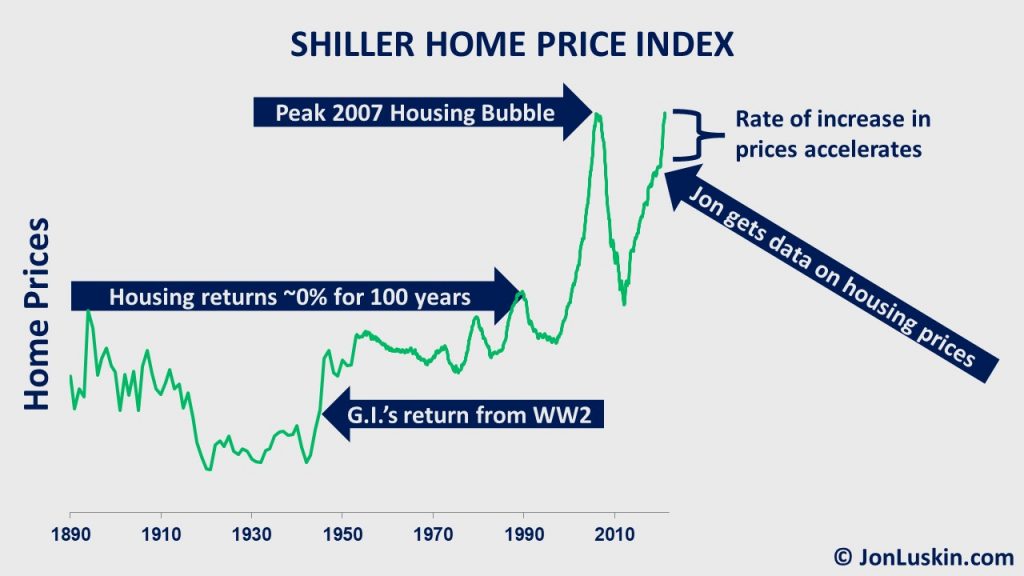

In the June 2021 issue of the Financial Planning Association’s Journal of Financial Planning, I wrote a short piece on housing. In the article, I pointed to the rise in prices. I argued that while housing has done well over the last couple of decades, that trend may not continue. Given that uncertainty, funding retirement by cashing out your primary residence is not a great idea.

Between gathering the data for that article earlier this year and today, the rate of increase in housing prices increased! What was increasing at a fast pace is now increasing even faster.

The absurdity is hard to ignore; what was expensive has become even more expensive.

Yet, this is how investing works; predicting future returns is notoriously difficult – if not impossible. That takeaway applies to all investments: stocks, bonds, and real estate.

(The same goes for gambling. No one knows what tomorrow holds for Bitcoin, Ethereum, or Beanie Babies.)

Table of Contents

Expected Investment Returns on Housing

Predicting investment returns in the short term is almost impossible. In the long term, we can get an idea of what’s possible.

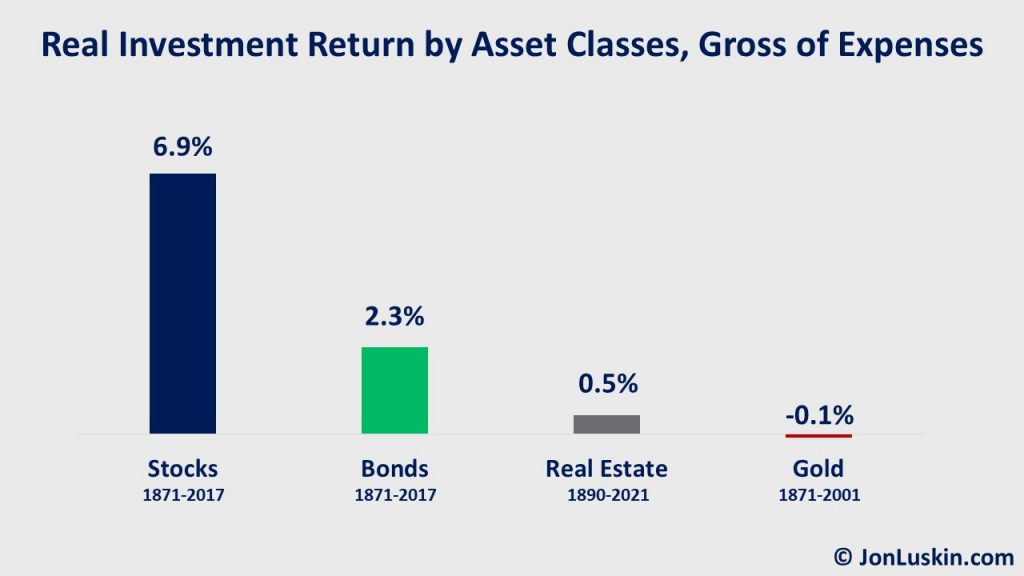

When there is more than a century of data available, we have an expectation – but not a guarantee – of future investment returns. The below chart shows how specific investments have performed over a very long time.

Even when ignoring costs, investing in real estate for appreciation alone hasn’t performed well – at least compared to the alternatives: stocks and bonds. Stocks have historically been a great investment (over a long time). With bonds, that’s less the case – but still more so than the appreciation on real estate.

Yet, when calculating the investment return on your personal residence, you very likely lost money after including the ongoing costs of homeownership.

The Costs of Investing

The numbers from the chart above are gross of expenses; the costs of investing are not included. Any Boglehead will tell you that is quite the oversight. That’s because managing costs is critical in investing; every dollar spent on costs is a gone dollar forever.

Fortunately, investment costs can be a less important consideration in stock and bond investing; you can invest in a no-cost stock index fund for free. Similarly, you can invest in a high-quality bond fund for just half of a tenth of a percent (0.05%).

However, the costs of other types of investments are still significant. The cheapest gold-backed ETF charges more than three times a low-cost Treasury fund. And while indirect real estate investing is possible with a low-cost REIT index fund, direct real estate costs are substantial.

Costs Impacts the Investment Return on Real Estate

Direct real estate investing is expensive; expect to pay ~1% in annual property taxes, and an additional 1% for maintenance every single year. You also need to add the cost of ongoing improvements, property and liability insurance, and possibly mortgage interest and mortgage insurance. If you’re using a middle-man (syndicate) to invest in direct real estate on your behalf, you’ll need to add in their 1% fee too.

Considering just the expenses of taxes and maintenance, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect a negative 1.5% investment return.

Historic Appreciation (0.5%) – property taxes (~1%) & maintenance (1%) = Negative 1.5%

In short, investing in direct real estate has significant costs. These costs decrease your investment return. Whether you are a professional real estate investor, or simply hoping to do well by your primary residence, the high costs of owning real estate detract from the investment return.

Mean Reversion in Investment Returns

So far, we’ve covered the ideas:

- The long-term price appreciation of real estate has been dwarfed not just by stocks, but bonds too.

- The above points ignore the very large costs of real estate investing. Once you factor in those costs, investors have historically lost money when betting on property appreciation.

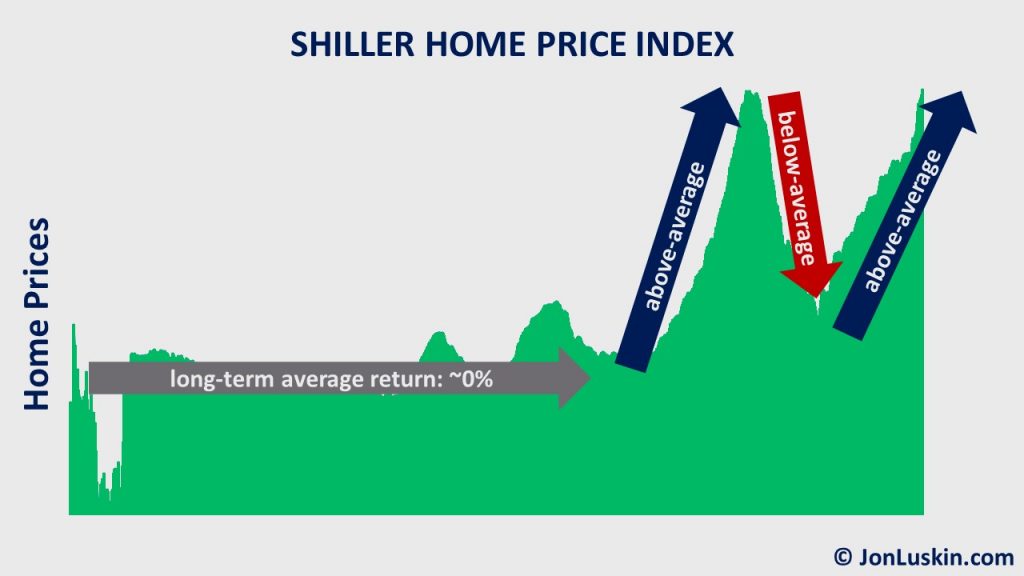

The above conclusions apply because – over very long timelines – the price increases of residential real estate aren’t great. Of course, that’s not what we’ve seen recently. Over the last couple of decades, real estate has provided unusually high investment returns. Said simply:

Recently, the performance of real estate has been above-average.

Given this recent above-average performance, we could expect the opposite in the long-term: below-average performance. Nerds call this mean reversion.

Don’t let this geeky term cause you to lose consciousness. Mean reversion is simply the nerd’s way of saying:

What goes up must come down.

And vice versa.

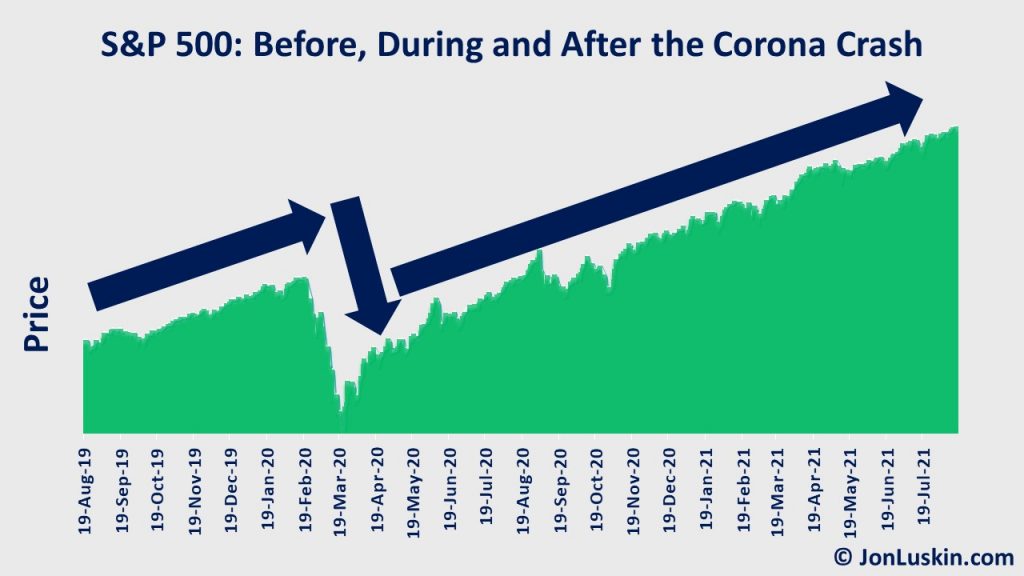

We see this with stocks all the time. Stocks go up. Then, they go down. And then, they go back up again. We just saw this happen with the corona crash.

We see these up-down-up movements with interest rates and bonds prices, too. And we’ve seen the rising and falling of prices of Beanie Babies, and cryptocurrency.

Mean-reversion (up-down-up) isn’t specific to just stocks, bonds, Bitcoin and Beanie Babies. It happens in real estate as well.

Consider the real estate bubble of two decades past: prices peaked in 2006, bottoming out in 2012. We’re now back to 2006 levels.

Therefore, if residential real estate has averaged 0.5% per year – when including the above-average price run-up of the last couple of decades – what does that suggest for the future? Through the lens of mean reversion, a case could be made for future negative returns on housing – even before considering the costs of ownership (property taxes, maintenance, mortgage interest, etc.).

I Don’t Gamble on Real Estate Appreciation

When it comes to the investment return available from real estate’s price appreciation alone, consider that the long-term average suggests a negative real investment return after expenses. Not just that, but the recent price run-up on residential real estate suggests that – eventually – this recent bonanza in housing prices may end.

In short, I am skeptical about housing prices continuing to increase at their current rate. And, I would not be surprised if housing prices held flat – or even dropped – in the future.

So, in the same way I advise clients not to expect their homes to provide for their retirement, I similarly suggest that money put into rental real estate does not depend solely on future price increases. Instead, your real estate investment should generate a fair bit of cash after expenses.

To be clear, I am a fan of rental real estate as an investment – with a couple of caveats. Firstly, invest in real estate directly yourself – don’t use an intermediary party (Roofstock, Fundrise, or other syndicates). That’s because – no matter the asset class – fees matter. And when you use a middleman to invest in direct real estate, the fees can be substantial. And as mentioned, your investment should produce cash.

I don’t suggest pouring money into a negative cash-flowing rental property, hoping that property can be sold for more money in the future. And I don’t suggest that you count on the growing equity of your primary residence to fund your retirement. Both strategies are speculative – and arguably unlikely to be successful given not only the long-term appreciation on real estate, but that more recent housing price appreciation.

Houses are Lifestyle Purchases

That’s not to say don’t buy a house – if you want a nice home for your family. Purchasing residential real estate is perfectly appropriate (if the price is within your means).

Said again: purchasing a home is OK as a lifestyle choice; it is not a guaranteed investment. Not only because historically real estate hasn’t done well on long timelines – even before expenses – but because mean reversion suggests that – at least for the next generation – a negative real return on housing is possible.

Said differently, I wouldn’t have the success of my financial plan be wholly dependent on further prices increases on residential real estate. Speculating on prices increases in real estate is fine – so long as if the amount at stake isn’t material to the success of your financial plan.

In the the article, I cover additional factors, such as interests rates and the impact of dual-income households on housing values. You can read my article in the Financial Planning Association’s Journal of Financial Planning here.

Postscript, I of II: But, I’ve Made So Much Money On My Home!

If you said anything like the above after reading this post, ask yourself:

Have I included the costs of property taxes, maintenance, insurance, mortgage interest, upgrades, inflation, etc., in my conclusion?

Probably not. When most humans “calculate” the investment return on their primary home, it goes something like:

Current Price in Inflated Dollars – Purchase Price = I made money

Any numbers nerd will tell you that you’re missing quite a bit in that formula. Whatsmore, that similarly misses the point that the irregular price run-up we’ve had in housing may not continue. But – if you’re betting your lifestyle in retirement on future price increases – then I hope that for you that the trend does indeed continue.

Postscript, II of II: You Didn’t Count Rent in Your Analysis!

I could do a whole other post on the rent vs. buy question. I won’t here now. (But, the quick answer is this: buy in low-cost-of-living (LCOL) areas, and rent in high-cost-of-living (HCOL) areas. The reason is the same you want to buy rental properties in LCOL areas, and shun HCOL areas if you’re not bullish on further price appreciation.)

Moreover, in the rent vs. buy equation, most tend to ignore the lifestyle inflation in that decision. For example, moving from a two-bedroom apartment to a four-bedroom house. This brings me back to my previous point: a house is a lifestyle purchase – and that’s ok.

My point is that while housing has done well over the last couple of decades, that trend may not continue. Moreover, even that past performance has conveniently ignored the very real costs of homeownership. Therefore, the plan fund-retirement-with-future-home-equity is not approved by this prudent financial planner.

Full cycle analysis. I agree with this perspective. However, I don’t the market momentum and typical leveraged selling RE Industry will approve.

Hopefully some will take heed and seriously consider your big picture.

Thanks !

Hello Albert,

Thanks for your comment.

Indeed, more than one type of investment can have cult-like followers. Real estate is no exception. Think gold and crypto.

When an analysis calls into question the value of an investment, feathers will get ruffled.

Hopefully, this post will be valuable for those do-it-yourself investors I work with – cautioning them that future returns on housing arent’ a guaranteed bet.

People so naive on investment value of RE. Bought a condo in a beach town on west coast just before covid. According to records paid 10% more than previous owner paid 15 years before. He didn’t make a dime on the place. Neither will I, but I don’t need or expect to. People are shocked by this. They shouldn’t be.

Hello Jim,

Thanks for your comment! 🙂

You’re doing it right. You’re going to enjoy that condo! But, you’re not betting the farm on it appreciating.

Whenever there is a good story, people lose their critical thinking skills. It’s not unique to real estate. It shows up every time humans want to believe.

The disposition to believing in a good story is what got us to where we are as a civilization today. But, it doesn’t always make for investing best practices. I somewhat talked about this idea here: https://jonluskin.com/story-people/.

Interesting piece on numbers vs story. I have a different take. It’s all stories, because even the numbers ride on stories. Beliefs about how theories such as Modern Portfolio Theory map to practical reality, or when, or if at all. I have no faith in my ability to judge numbers except on the margins. I have little faith in the ability of others to judge numbers except on the margins, because I see the stories beneath them they’re confident in that I’m not. Warren Buffet has said how Munger changed his mind about quantity over quality, and after that he thought company quality and relative competitive advantage was more important. Ideally I’d want a screaming good long-term buy–where I don’t need to run the numbers–early in my investment career. Say IBM in the 60s-70s, or their successor MS in the 80s, or Apple in the 00s. Hold on for decades. Lacking a perception of such a great story I’d invest in index funds and let someone else worry about the numbers.

I think what investments advisors miss is the fact that buying a house for most average ppl is done via a mortgage. With 10% down, you are leveraged 1 to 10. If it grows even with rate of inflation, you are essentially making 20% a year on your investment. Long-term this is also pretty low risk (there are no margin calls, etc.). So, many ppl realize that and that is why this whole run up of prices is happening… i am not even mentioning unprecedented printing of money happening, with real estate one of the very few real assets

Hi Jon, great article and insights as always. Given low interest rates and exponential home price appreciation over the last 18 months, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on individuals taking a cash-out refinance on their homes to invest/leverage the money elsewhere. I believe Michael Batnick and Ben Carlson from RWM talked about how they’re both employing this strategy per the recommendation of their firm’s advisor.

Hello Thomas,

Thanks for your kind comment. 🙂

That’s a great question.

It can make sense for investors with 100% stock allocations to leverage their investment portfolio by *not* pre-paying their debt. However, for investors with relatively less aggressive allocations (those holding any amount of bonds), holding debt means settling for a smaller investment return while bearing the same amount of risk as their 100% stock allocation peers. Said simply: holding debt while investing in bonds means enduring the same risk for less return. That’s why pre-paying debt can make sense for investors who *don’t* have 100% stock allocations.

To be clear, this takeaway is independent of home appreciation or even low rates; it’s simply an issue of capitalizing on the risk premium.

Michael Kitces does a great job explaining this here: https://www.kitces.com/blog/why-is-it-risky-to-buy-stocks-on-margin-but-prudent-to-buy-them-on-mortgage/