Stocks are down. Bonds are down. High inflation means cash is losing value. There are forecasts of a 1% further increase in interest rates. What is an investor to do?

Here are six strategies for investing in a rising interest rate environment – sorted from Absolutely Terrible to My Personal Favorite.

A>Alternative Assets: Absolutely Terrible

There’s been talk on the Twittersphere about the 60/40 portfolio being dead.

The argument is that one should move out of traditional stocks and bonds and into something else. Let’s see how the pros and cons of this strategy stack up.

Pros

None.

Cons

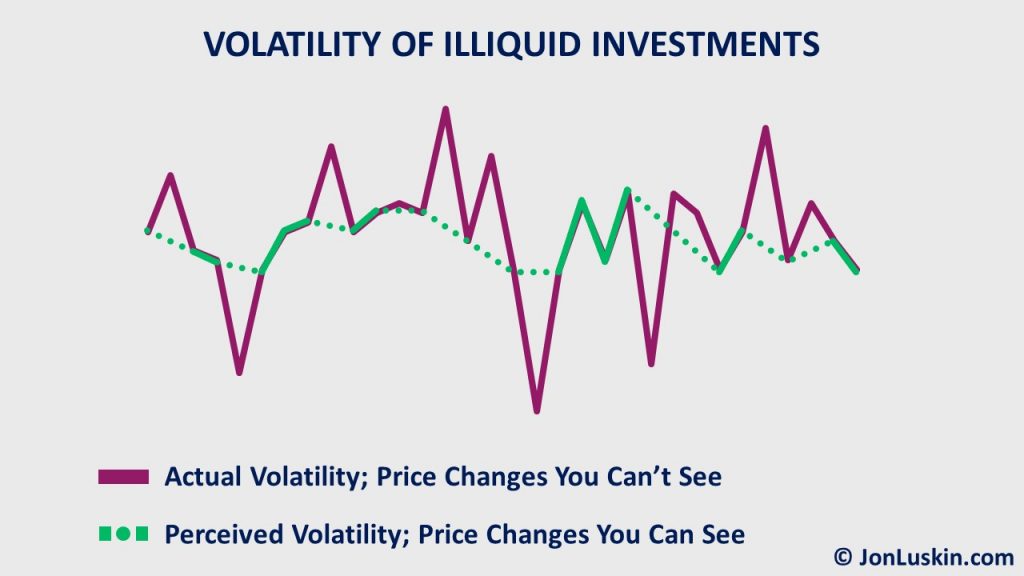

Alternatives are touted to provide diversification, but that’s often simply a misunderstanding of liquidity. For example, endowments heavily invested in alternatives saw their portfolios plummet during the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

That is to say: Alternative investments tell a compelling story. However, the data shows that alternatives don’t deliver on their promise of high returns. I’ve only ever seen portfolios containing alternatives underperform a portfolio of low-cost index funds. (Read another case study on the failure of alternatives here.)

In short, investing in alternatives doesn’t guarantee performance. But it does guarantee paying more in fees. What’s more, the nature of alternatives frequently also means higher taxes. That’s why investors are generally best off shunning alternatives.

Sell Bonds for Stocks: Generally >Sell Bonds for Stocks: Generally Terrible

orst things an investor can do – at least, if they’re trying to manage risk. To manage interest rate risk, investors in bonds can move to stocks.Pros

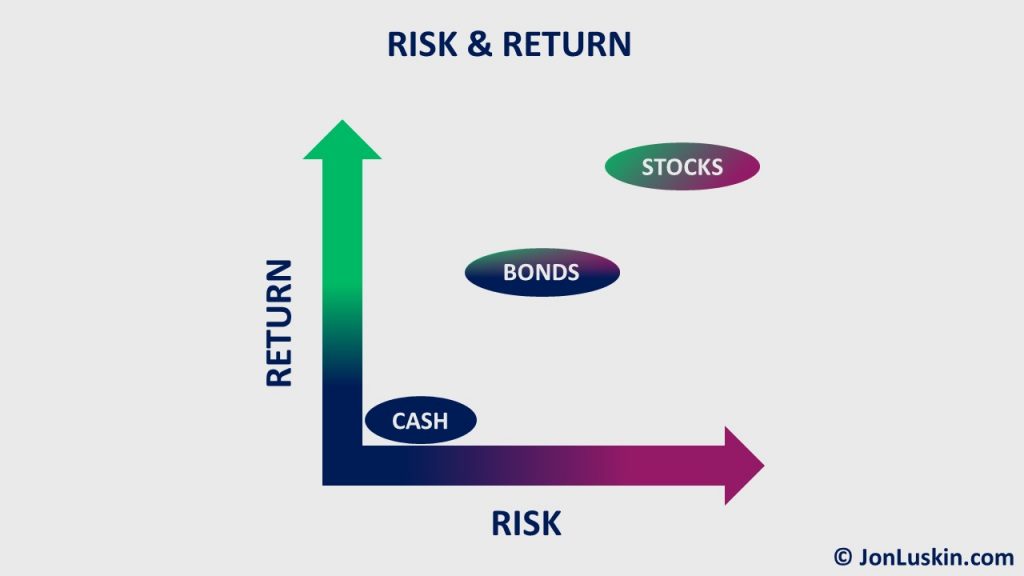

The upside to this strategy is the upside; stocks have a greater investment return potential than bonds.

Cons

With increased returns comes increased risk. Moving from bonds to stocks to manage interest rate risk means taking on the much more significant consequences of stock market risk; you stand to lose a lot more in stocks than you could ever lose in bonds.

Over the last ~12 months, high-quality intermediate-term bonds have lost more than any time in recent history. Those unprecedented losses are in the low double-digits. Over the same period, stocks lost roughly twice that. During other market panics, stocks have done even worse:

- A couple of years back, stocks lost ~30% during the coronavirus-inspired crash.

- During the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009, stocks lost ~50%.

- During the tech bubble fallout of 2000-2002, stocks lost ~48%. Tech stocks did even worse.

- And, during the market crash that set off the Great Depression, stocks lost ~90%.

Which is to say, you can – and sometimes will – lose money in bonds. But, investors often lose a lot more in stocks.

Bonds are Not Stocks

I had Rick Ferri, CFA as my co-host for the first episode of the Bogleheads® Live series. Rick said something that I won’t soon forget:

Bonds are not stocks. Even though now is probably the worst time to invest in bonds, it’s still a place to put money that isn’t stocks.

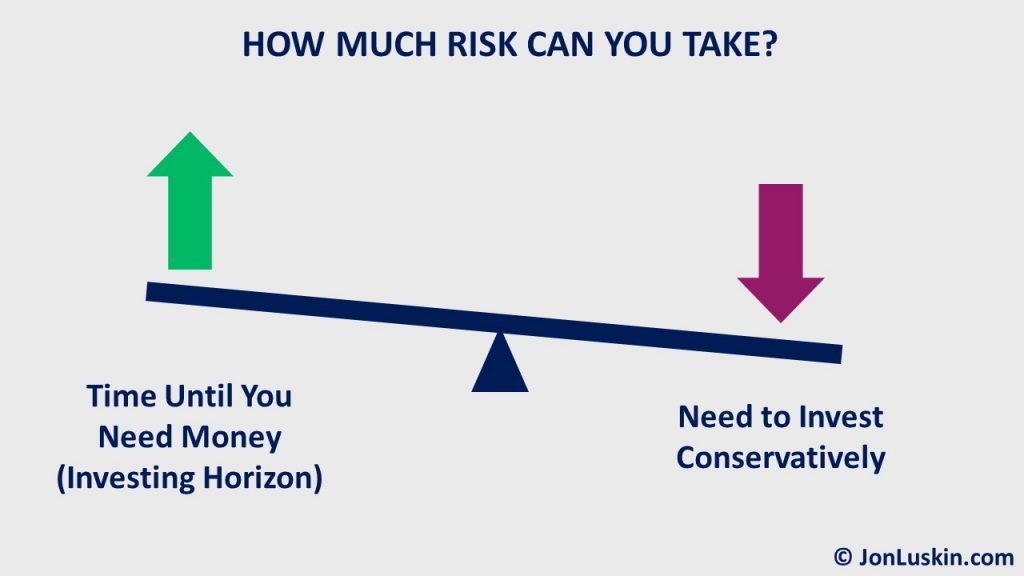

I’ve scored the bonds→stocks strategy as generally terrible, as opposed to absolutely terrible. That’s because it might not be the worst option for very young investors.

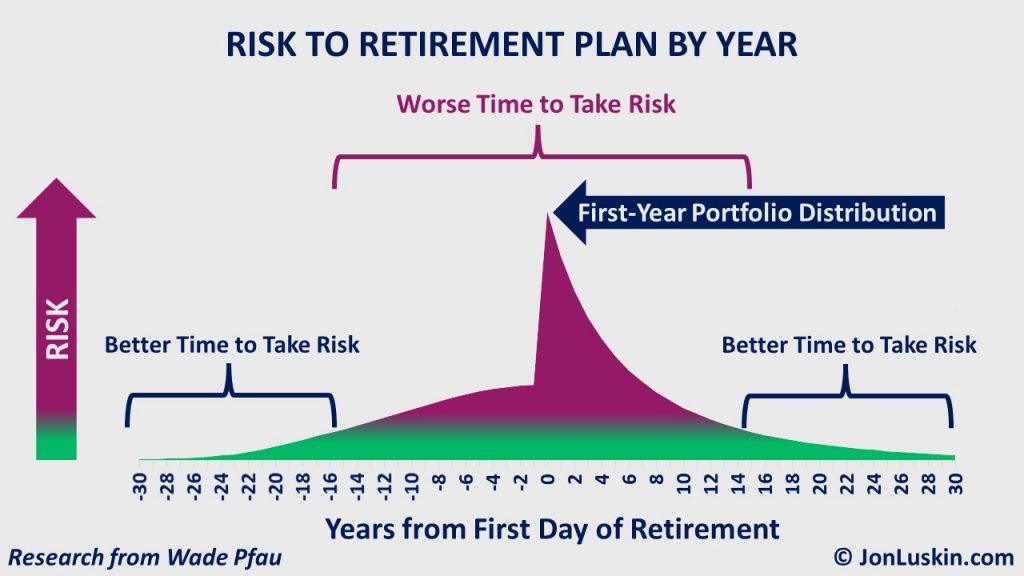

For those on the cusp of retirement, moving from bonds to stocks is problematic. That’s because the first day of retirement is the riskiest. At that point, selling at a market bottom greatly impacts the success of your retirement plan.

Generally, investors can manage this risk by overweighting bonds at the outset of retirement. (This is the same approach used by target-date funds.) Yet, ditching bonds in favor of stocks means increasing risk. That may be a disaster for those at the outset of retirement.

Move to Cash: Very Bad

When selling investmen>Move to Cash: Very Bade out of the market. This is classic market timing. In anticipation of further market declines – whether in the stock or bond market – investors sell their positions to avoid further possible investment losses.

Pros

You’ve successfully managed risk in the short term. This can be emotionally comforting.

Cons

By sitting in cash, you’ve taken on the long-term risk of inflation. Moreover, investors engaging in market timing are likely to get it wrong – selling at the bottom, only to buy back in at the top. Or, they never get back in at all.

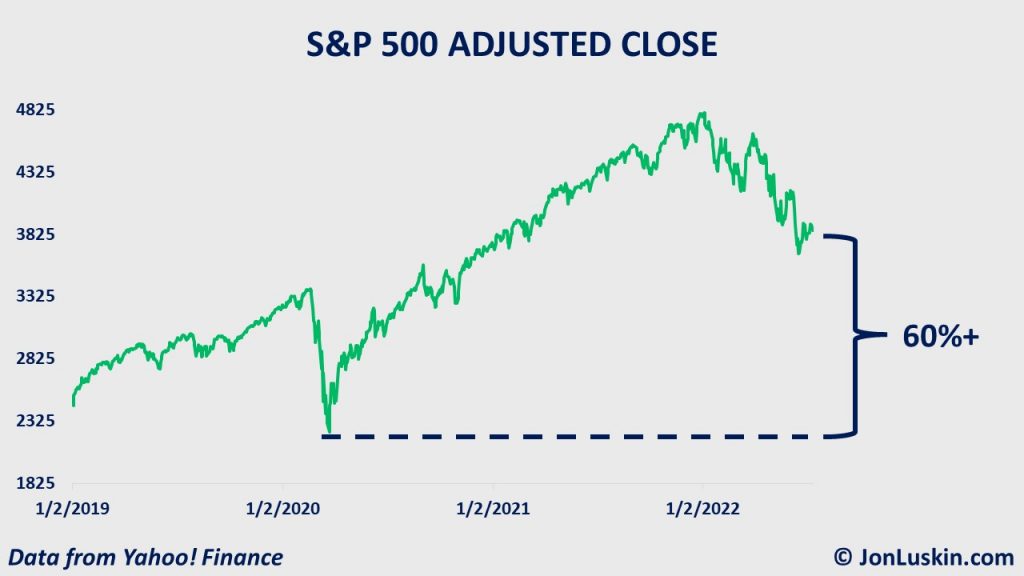

Recently, at my local investing meetup, one investor shared that he sold during the turmoil of the coronavirus. He has yet to get back in. Had he gotten out at the bottom in March of 2020, he would have given up more than 60% growth between then and now.

Not being invested means losing out on future market returns. And – at least in the past – being invested meant being rewarded.

Move from Intermediate- to Short-Term Bonds: Bad

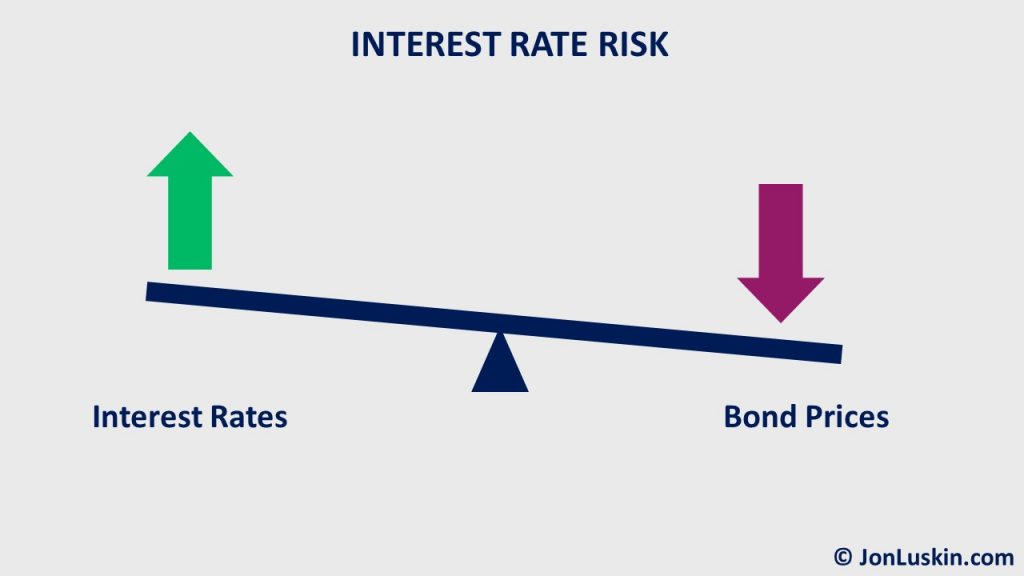

The idea h>Move from Intermediate- to Short-Term Bonds: Bad rates. (This and the strategy above are related. You can consider cash an ultra-short-term U.S. government bond.)

Pros

You’ve decreased losses from further interest rate risk. You’re also still invested.

Cons

“It’s probably not a great idea to dump all of your intermediate-term bond holdings in favor of short-term, or switch from bonds to cash. Simply put, you’re probably too late.”

~ Christine Benz, Director of Personal Finance, senior columnist for Morningstar

Unfortunately, as with the market-timing strategy above, the same challenge remains: you have to get the timing right. And, that’s really difficult.

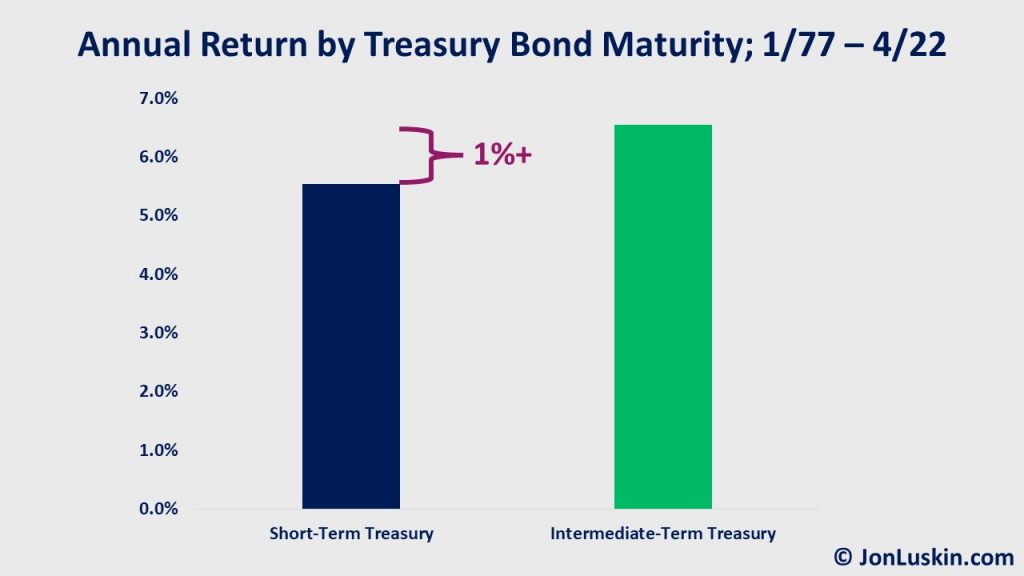

Moreover, moving to shorter-term bonds means missing out on the larger interest payments of intermediate-term bonds. That likely means you’ll need to settle for a smaller investment return. Benz touched on this in the fifth episode of Bogleheads® Live, discussing how holding a portion of your portfolio in cash means settling for a lower distribution rate in retirement.

Tactical Bond Allocation: Not My First Choice

Larry Swedroe has been quoted referencing a strategy of Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA): only holding longer maturity bonds given sufficient additional yield. A white paper on the subject from DFA reads:

Investors can vary duration within a window: shortening maturities when term spreads are narrow and term premiums are expected to be small; extending them when term spreads are wide, indicating a larger term premium.

Said differently: you systematically change your bond portfolio as interest rates change. When I wrote Larry an email asking about just this, he wrote back to caution against a too-literal interpretation of the two-basis-points-per-month rule. Instead, he suggested staying within a range of maturities, between three and seven years.

Moreover, the keyword of the last paragraph is systematically. That is, you won’t be moving from intermediate- to short-term bonds because someone mentioned “the Fed something something” on Twitter. To be successful, you’ll stick to a rigorous approach.

Options for Implementation

If using a variable maturity approach, investors have three main options:

- moving between individual Treasuries

- moving between low-cost Treasury funds of various targeted maturities

- buying and holding a variable-maturity bond fund

A final option – not generally recommended – is a separately managed account (SMA). Given the fees of SMAs, I am skeptical that investors can get ahead by paying a lot more.

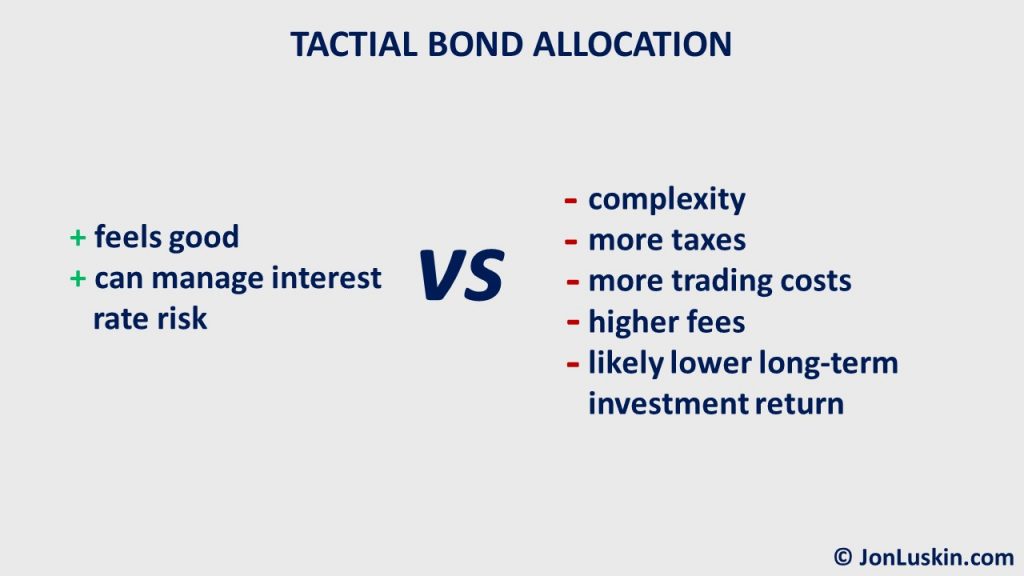

Pros

There is some emotional comfort in continually managing a portfolio (or having it managed) rather than simply riding down the losses in bonds. As another pro, the advent of the iShares series of ‘bullet’ bond exchange-traded funds (ETF) makes roughly targeting a particular maturity with a Treasury bond fund easier than purchasing individual Treasuries.

For those who want to take on credit risk (I prefer not to), DFA’s Core Fixed Income ETF (DFCF) uses a variable maturity approach, pursuing the term premium when that premium is relatively larger. (It takes the same approach with the credit premium, too.)

Cons (There are a lot of them.)

If managing the process yourself using individual bonds or rotating between bond funds of various maturities, that’s complicated. Tactical bond allocation requires additional work; one must stay up-to-date on the yield curve and adjust their bond portfolio accordingly.

In short, it’s complicated. It’s often said that the best strategy is the one that you can stick with. Additional complexity makes sticking with a strategy more difficult.

Second, more trading means more costs; there may be additional taxes in selling a bond (fund) that’s increased in value to buy another bond (fund) that better matches your targeted maturity. There’s also transaction costs from crossing the bid/ask spread.

If using ETFs, there’s an increased risk of buying an ETF at a premium. Dr. William Bernstein touches on some of the challenges of trading bond ETFs on the 8th episode of Bogleheads® Live.

Third, you’ll pay slightly more in fund fees – if using funds, instead of individual bonds. For example, the iShares series is almost twice Vanguard’s intermediate-term Treasury fund. (But, to be fair, we’re only talking three basis points (0.03%), or $3 more in annual fees for every $10,000 invested.) DFA’s fund mentioned above is even more expensive; almost five times the Vanguard fund mentioned above.

Fourth, compared to short-term bonds, investors can eventually come out ahead by investing in relatively longer (intermediate-term) bonds. Whether investors can earn more by using a variable-maturity approach – avoiding the short-term losses from rising interest rates – is unlikely.

More from that same DFA white paper:

A variable-maturity approach has led to a better tradeoff between return and expected volatility than strategies that maintain a constant-term exposure.

The key word is tradeoff. That is, you probably won’t make more money. Yet, your risk-adjusted return might be better. (That might suggest that if using a variable maturity approach to bonds, you should hold slightly more stocks instead. The increased return and risk of holding more stocks might result in a superior portfolio.)

Finally, when rotating between the various iShares series of funds, you can’t precisely target your bond allocation. To do that, you’ll need to buy individual bonds. While that’s not exceptionally difficult, it’s not for everyone.

Perhaps in the future, DFA will launch a variable-maturity Treasury ETF. To better manage interest rate risk, that might be worth considering for those investors willing:

- to pay more in taxes,

- to pay more in fees, and

- to settle for a smaller investment return.

Stay the Course: My Personal Favorite

Stay the Course: My Personal Favoritee, founder of Vanguard

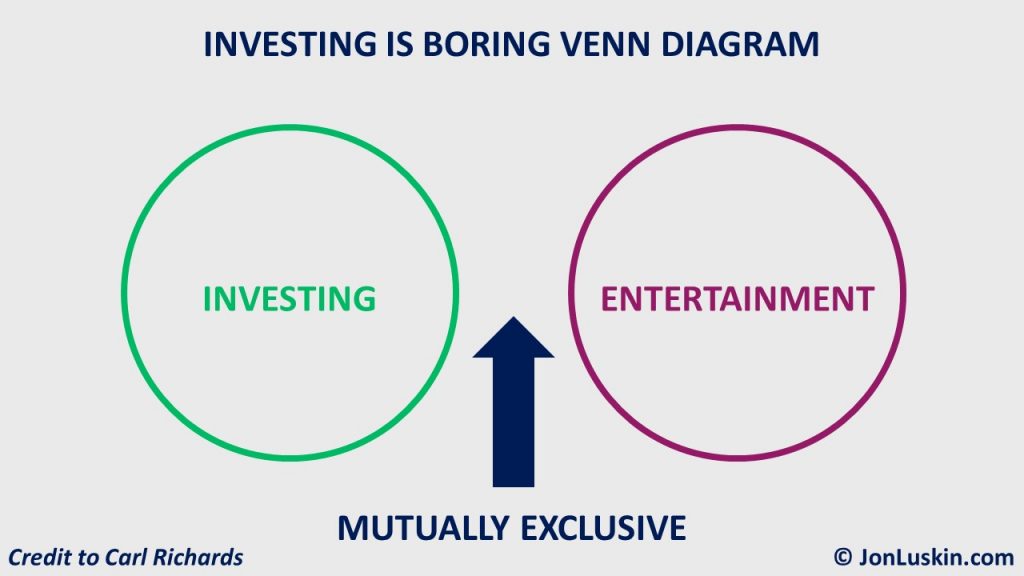

You continue with your investment plan as before, reviewing your portfolio perhaps annually and rebalancing if necessary. This is the most boring strategy. But, I like my investments boring.

Pros

It’s simple. Staying the course requires the least effort. It can also decrease taxes. I know that with patience, I’ll eventually make back any losses from holding intermediate-term bonds by collecting the now-larger interest payments. And finally, staying the course is the best way to avoid human error.

Cons

While this strategy is technically simple, it’s not emotionally easy. The hard part is what you’re not doing: nothing. That is, it can be emotionally difficult to stick with your investment plan, to not tinker or make changes in response to the latest market movement. Yet, those two things are essential to success: patience and discipline.

The Bogleheads® Bias for Simplicity

“Simple beats complicated when it comes to investing.”

~Christine Benz

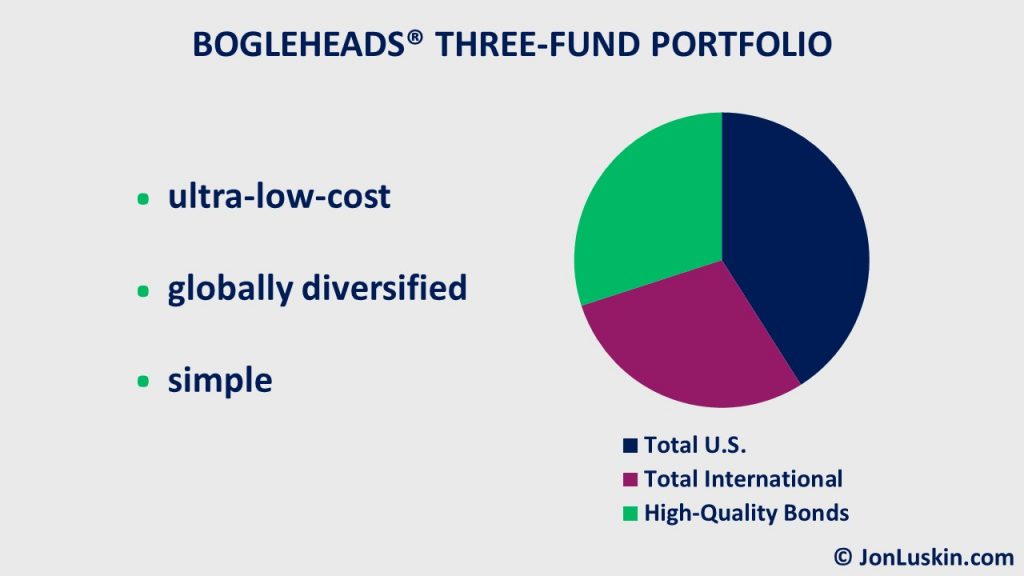

Recently, I worked with a family who moved away from their traditional high-fee asset manager. They decided to manage their investments themselves, using low-cost index funds. Unfortunately for them, they decided to use a lot of low-cost index funds – slicing and dicing what would otherwise be two low-cost stock funds.

They confided that they regretted that decision as soon as it came time to do their first rebalance. Generally, two low-cost stock funds are all one needs.

That’s why I’m biased towards simplicity: embracing simplicity helps ensure investing success. Of course, I’m not alone in this approach. Many Bogleheads® have a bias towards simplicity:

- Mike Piper, CPA uses a single, low-cost balanced mutual fund in his tax-advantaged investment accounts. He spoke about this on the 9th episode of Bogleheads® Live.

- Dr. William J. Bernstein suggested the topic for the 8th episode of Bogleheads® Live, the importance of simplicity when investing.

- Rick Ferri, CFA, on the 2nd episode of Bogleheads® Live, shared how his investment approach has changed over time, since he wrote All About Asset Allocation years ago:

In the All About Asset Allocation book, I think I used eight, nine, ten different funds. For example, I divided Europe, Pacific, and emerging markets into three different pots of money. I was showing that there may be some benefit to having three different funds, rather than just having one total international fund.

I’ve gone away from that. Even if there is an incremental benefit to doing that, it’s much easier to have a total international index fund.

Bonus Strategy: Cowboy Account for Market Timing, Alternative Assets, and More

I realize that my preferred route is the one approach requiri>Bonus Strategy: Cowboy Account for Market Timing, Alternative Assets, and Moreconsider a split strategy:

- With most of your money, stay the course.

- Then, take a little bit of money to fund a cowboy account – where you do any number of ill-advised strategies.

Playing with (lighting on fire) a little bit of money is reasonable – especially if it means that you stay the course via the tried-and-true, boring approach with the bulk of your investments.

Disclaimer: For education and entertainment purposes only. Not specific investment advice. Confer with your tax and investment professionals before making any investment decisions.

Great article!

Thank you, Jim!

I’ll be linking to this post in my blog this week! Well done!

Thank you, Holly!

It’s certainly a timely topic!

Best wishes,

Jon